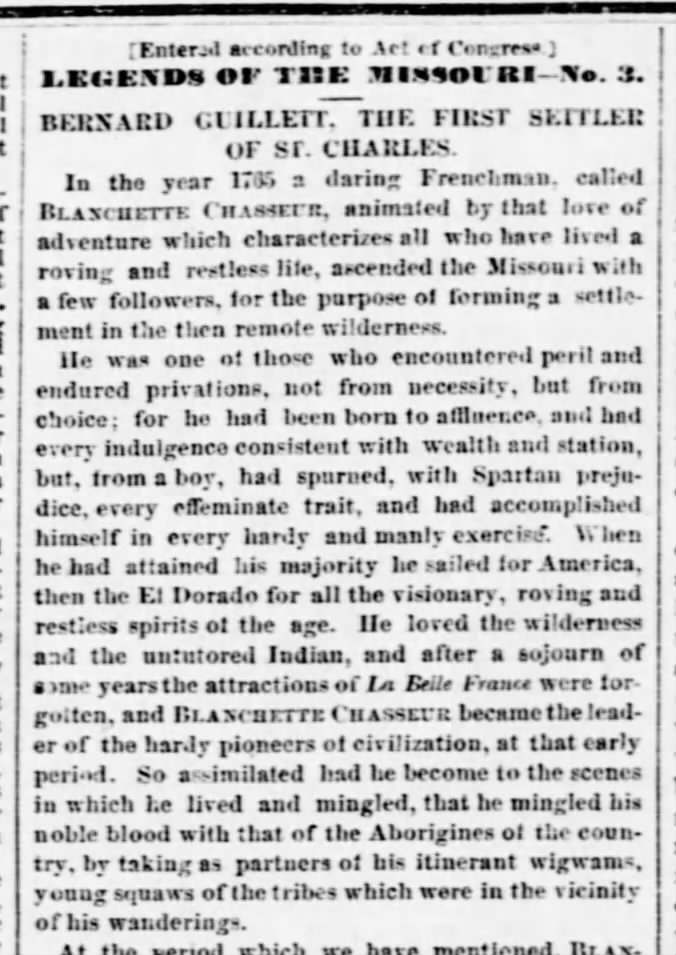

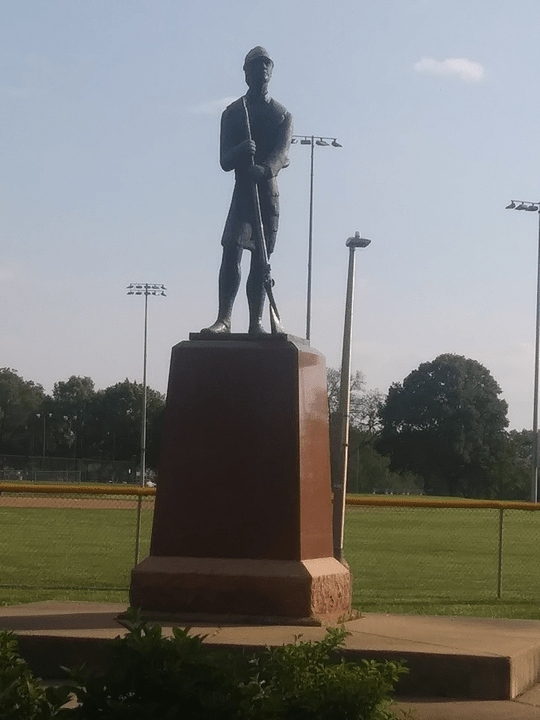

The singing in fledgling barbershop chapters is not always the best, but there is a fun camaraderie that can be formed in singing together. In 1970, the Daniel Boone Chorus marked its seventh anniversary. The chapter experienced some ups and downs in the 1970s but survived the decade in preparation for what lay ahead next.

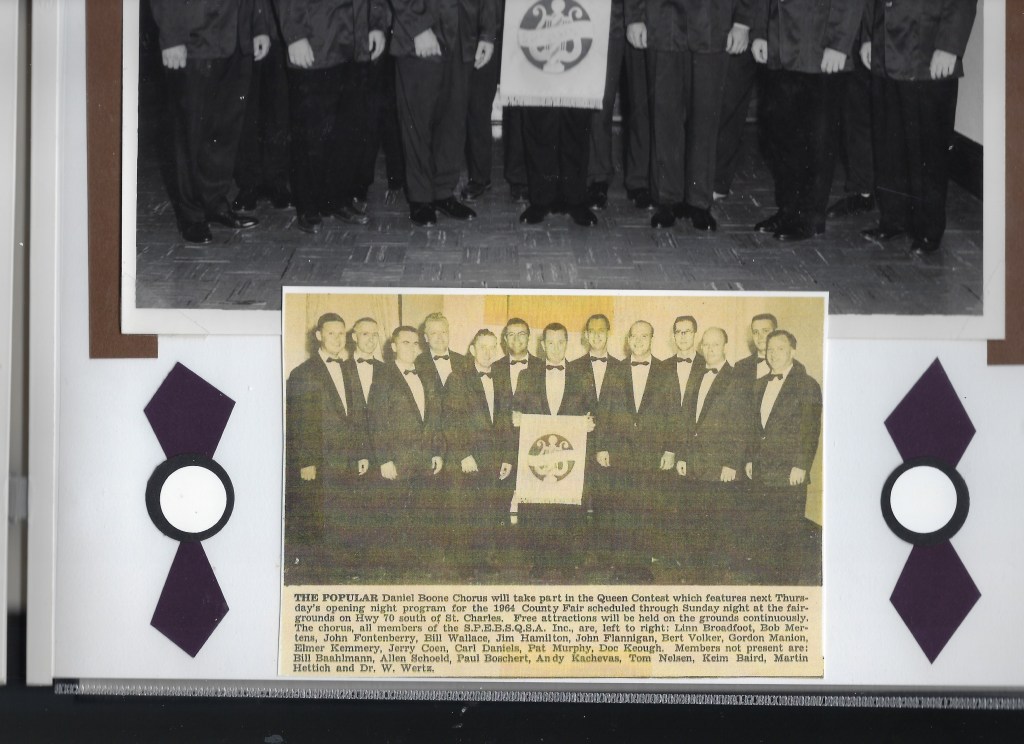

Jerry Coen served a second term as board president in 1970.[1] Junior Fisher was Administrative Vice-President, Larry Groeblinghoff was Program Vice-President, Don Clark was Secretary, Bill Morton was treasurer, Larry White was Bulletin Editor, Bob Henry was in charge of Public Relations, and Roy Seigler (1927-1997) served as the chapter contact. Coen, Fisher, Groeblinghoff, and Henry attended the Chapter Officers Training School in Lincoln, Nebraska, on 17-18 January 1970. [2] 5-11 April was Barbershop Harmony Week, again by proclamation of Mayor Henry C. Vogt (1903-1992) of St. Charles.[3] Jerry Coen gave a gushing report to the chorus over the June show. He singled out Dave Moorlag for promoting the location of the show as the St. Charles Cinema and Woody Ashlock, who wrote the show, was M.C., helped with scenery, painted most of it, put an act in the show, and directed the show.[4] The show was presented on 11 June 1970.[5] On 29 July, the chapter hosted “St. Charles Style Jamboree” at the new Knights of Columbus Hall at 3 Westbury Drive in St. Charles.[6] The “non-fishing trip” continued as an annual Labor Day event.[7] The chorus posted a second-place finish at the St. Louis Area Barbershop Chorus Contest in 1970.[8] However, they finished first in the Small Chorus Competition at the Central States District in Davenport, Iowa later that year.[9] The chorus received a trophy for being the best chorus with less than thirty men.[10] The chorus finished tenth overall at that competition, which was held on 17 October.[11] The chapter allowed the St. Charles Sweet Adeline Chapter to borrow sets and props for their show.[12] The chorus participated in the 22nd Annual Parade of Harmony, presented by St. Louis No. 1 Chapter, Saturday, 7 November 1970 at 8 p.m. at the Kiel Opera House in St. Louis.[13] The St. Charles Chapter held a coon hunt on 13 November 1970 in St. Paul, Missouri.[14] The Daniel Boone Chorus won the Christmas Caroling Contest, held from Thanksgiving to Christmas. Four singing groups entered the contest, “singing on separate evenings.” Capt. George Overly of the Salvation Army presented a plaque to Board President Jerry Coen.[15]

In January 1971, new chapter officers were selected by the chapter members. The new officers were installed at the Mother-in-Law House in St. Charles.[16] William Earl “Bill” Morton (1930-1991) was president, Donald Ray “Don” Spiegel (1929-2003) was vice-president of administration, Ralph Joseph Fisher (1927-1988) was vice-president of programming, Col. Kenneth Arthur “Ken” Schroer (1939-2015) was secretary, Bert Volker was treasurer, Gerald Mohr was bulletin editor, Robert Elwin “Bob” Henry (1936-1980) was District Area Counselor, and Howard Vane “H. V.” Jacobs (1935-2003) was in charge of the chapter’s public relations.[17] A picture of the chapter leadership was taken in front of the Nebraska Center for Continuing Education in Lincoln, Nebraska, where they attended to COTS.[18] Some pictures of a 1971 board meeting are in the Daniel Boone Chorus, 1970-1971, binder in the chorus’ archives. Newcomer Robert “Bob” Hall oversaw uniforms.[19] Bill Morton, prior to becoming Chapter President, was Chapter Secretary and Treasurer in 1969 and 1970. He developed a bookkeeping and record maintenance system for the chapter board. He was the first chapter president to bring the chapter in debt. The debt was accrued from the purchase of a professional sound system. Morton used his basement to store chapter equipment. He was Co-Chairman of Registration for the 1969 International Barbershop Convention in St. Louis and served as Treasurer of the St. Louis Area Barbershop Council in 1972 and 1973. He was known for having an analytical mind and keen eye for organization. He worked as a production planner for McDonnell Douglas.[20] The chorus performed at the O’Fallon Sweet Adelines Guest Night on Monday, 13 February 1971 at 7:30 p.m. at St. Dominic High School in O’Fallon.[21] The Daniel Boone Chorus launched Operation HARMONY (Hope And Rehabilitation Means One of us Needs You) in 1971 to help a thirty-four-year-old man who had recently had surgery to remove a brain tumor. The family could not afford bills, so the chorus decided they would raise money to help.[22] The 1st Annual Barbershop Show-Dance presented by the St. Charles Barbershop Choirs and Quartets was at the Community Club Building in Wentzville, MO, at 8 p.m. on Saturday, 20 March.[23] It was for the Optimists Club of Wentzville.[24] The chorus was hosted by the Mark Twain Merchants Association. “The best little chapter in the Central States District” performed at the Mark Twain Shopping Center during Barbershop Harmony Week (11-17 April) in 1971.[25] In May, the chorus performed for Our Lady of the Presentation Church of St. John, Missouri.[26] Mutual Funs, a quartet consisting of members of the St. Charles Chapter (Bob Henry and Bert Volker), and members of the St. Louis Chapter (John Jewell and Ron Grooters) performed in “The Music Man” at the St. Louis Muny from 26 July to 1 August 1971.[27]

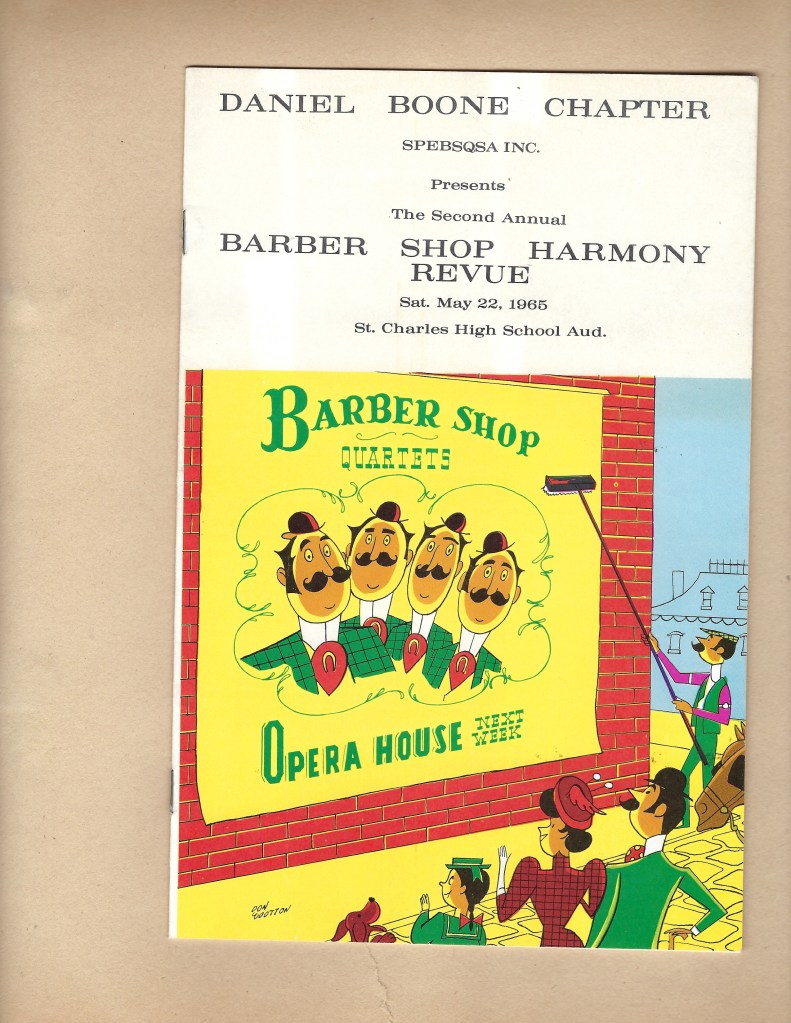

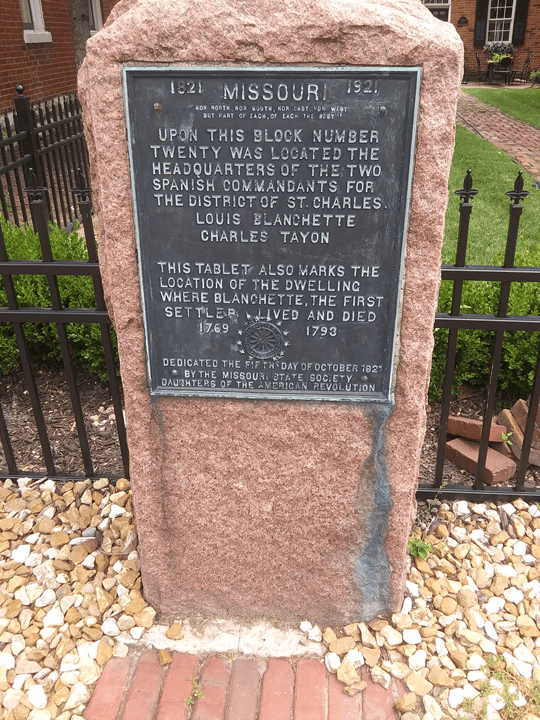

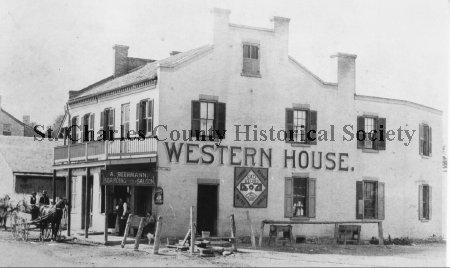

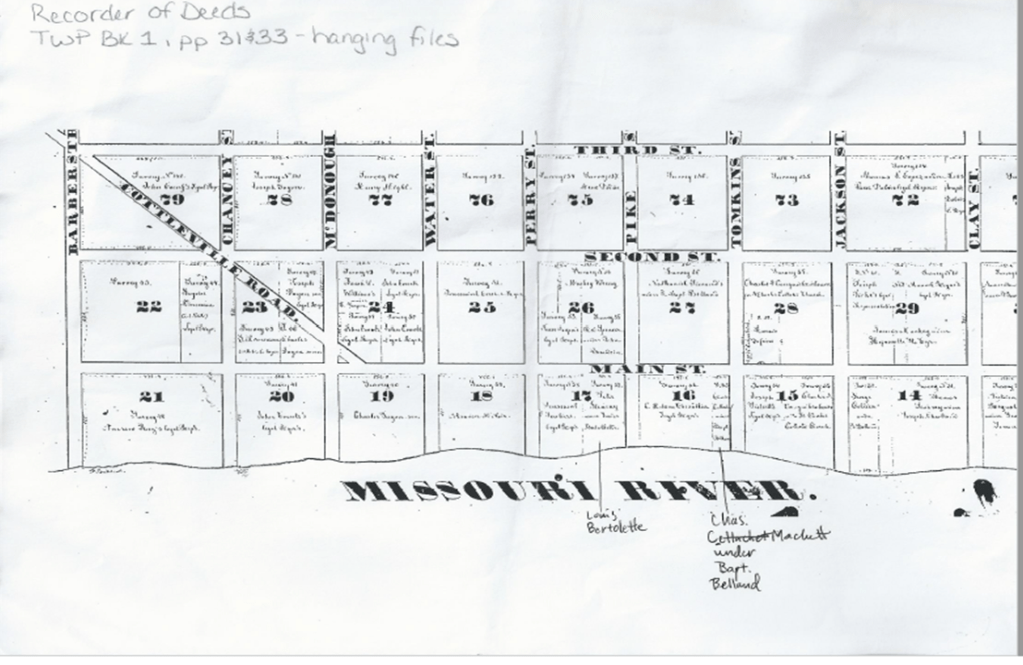

The chorus sponsored a float in the Missouri Sesquicentennial Parade of 1971. This is the only photo of the Daniel Boone Chorus in the possession of the St. Charles County Historical Society.[28] The St. Louis Area Barbershop Contest was held at Webster Junior High School in Collinsville, Illinois, on 11 September 1971.[29] The Daniel Boone Chorus finished thirteenth in the Central States District Chorus Competition at Wichita, Kansas, on 2 October.[30] Gordon Manion turned over the reins of directorship to Carl Daniel in October 1971.[31] The chorus announced a new director in December 1971. Donald Joe “Don” Nevins (1942-2003) taught music at Central Junior High School in the Riverview Gardens School District and previously had directed the Alton (IL) Barbershop Chorus, the St. Louis Archway Chorus, and the Overland Sweet Adelines Chorus. His quartet experience included the Boot N Aires of Bloomington, Illinois, and the Hartsmen of Illinois. He won the St. Louis District Metropolitan Opera Auditions in 1969 and 1971, performed with the Mississippi Valley Opera Company, and sang at the First Church of Christian Science of St. Louis and the Temple Shaare Emeth in St. Louis. At the time, Nevins became director of the Daniel Boone Chorus, the St. Charles Chapter boasted fifty members and was rehearsing on Wednesday nights at St. John’s United Church of Christ’s Church Hall at Fifth and Jackson streets in St. Charles.[32]

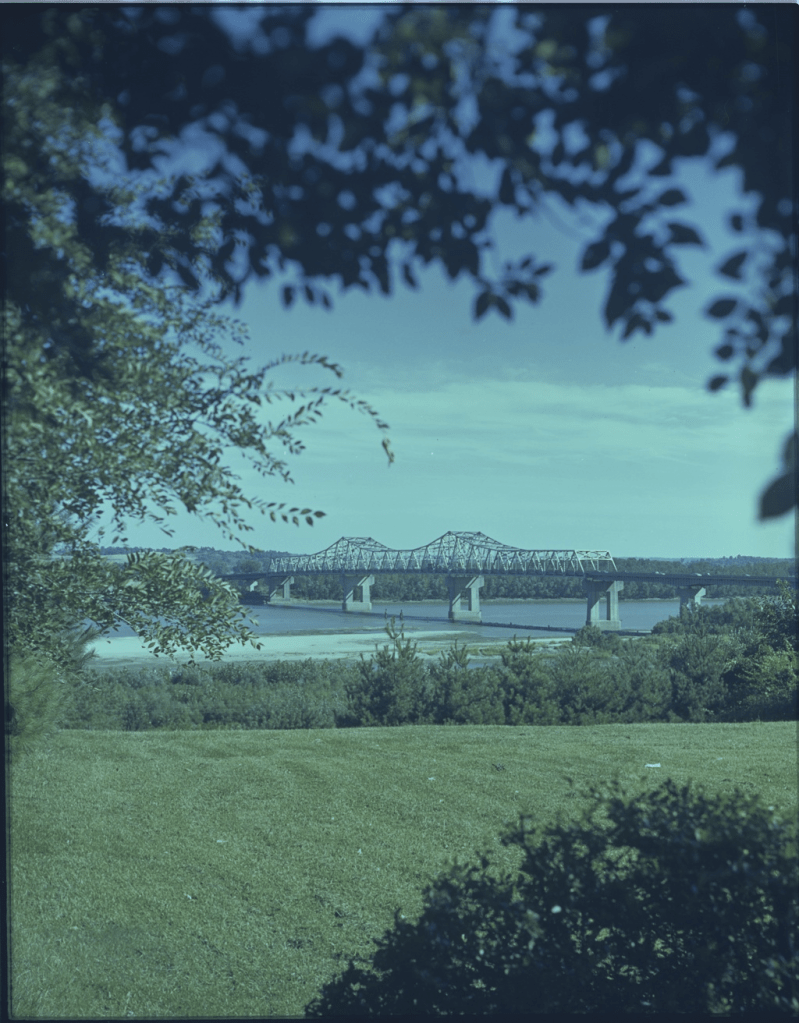

From 1972 to 1973, Ken Schroer was St. Charles Chapter Board President. Kenneth Arthur Schroer was born on 2 December 1939 in St. Louis to Arthur John and Mabel (McGahan) Schroer. He was a colonel in the United States Air Force.[33] He formed a bylaws committee to establish a firm set of guidelines for future chapter boards. He served as board secretary, on the public relations committee, was a St. Louis Area Councilor in 1974, and was the Central States District Chairman for International Hospitality in 1974 and 1975. He served on the CSD Long Range Planning Committee and was CSD President in 1978.[34] On 19 February 1972, the St. Charles Chapter of S.P.E.B.S.Q.S.A. hosted “An Evening of Barbershop” at the Kiel Opera House at 8 p.m. The show featured the six-time Central States District Champion, the Pony Expressmen Chorus of St. Joseph, Missouri; the four-time St. Louis Area Champion, the St. Louis Suburban Chorus; Central States District Small Chorus Champion, the Daniel Boone Chorus; 1971 Central States District Quartet Champion, the Mid-Continentals; 1971 Central States District medalists, the Men of a Chord; and the Key Pickers.[35] On 1 March 1972, the chorus held a guest night.[36] The chorus performed far and wide in the community, including bi-monthly at the Emmaus Home in St. Charles. At Christmastime, the chorus would go caroling.[37] In June 1972, chorus members pitched in to paint the newly opened St. Charles Youth Center.[38] The Daniel Boone Chorus was involved in the Festival of the Little Hills beginning in August 1972.[39] This eventually became an annual affair in which they gave back to the local community by serving up music, food, and beer at the Festival of the Little Hills.[40] The chorus co-sponsored, with the St. Charles County Sheriff’s Rescue Squad, a beer garden along the riverfront on property recently purchased by the City of St. Charles for a riverfront park.[41] The chorus maintained its presence at the festival until 2002. The following month, the chorus performed at the Civic Park Pavilion.[42] During the weekend of 6-8 October 1972, the chorus (now boasting 54 members) finished in tenth place at the Central States District Chorus Contest in Des Moines, Iowa.[43] On 11 November 1972, the Daniel Boone Chorus performed for the Joseph L. Mudd Parent-Teacher Club at the J. L. Mudd School in O’Fallon, Missouri.[44] On 29 November 1972, the chorus hosted the Fifth Wednesday Jamboree at the Knights of Columbus Hall in St. Charles. Participants included S.P.E.B.S.Q.S.A St. Louis Suburban, Florissant Valley, Kirkwood, St. Louis No. 1, and Collinsville (IL) chapters. Among the quartets who performed were Men of a Chord, Gaslight Squires, the Gadabouts, and the Pea Pickers.[45] The Daniel Boone Chorus finished in tenth place in the Central States District Chorus Competition in 1972.[46] The chorus had the Daniel Boone Chorus Auxiliary, a group of wives who supported their husbands in singing barbershop. The auxiliary was renamed the Becky Boone Tagalongs in 1973.[47] The chapter currently does not have an auxiliary for the spouses of chorus members, but the Ambassadors Circle could be considered a successor to such auxiliaries.

1973 brought more milestones for the chorus. The Daniel Boone Chorus held a Guest Night in March.[48] The chorus raised $672 for the St. Charles County Sheriff’s Reserve at the Festival of the Little Hills in 1973. By that time, Ken Schroer was president and Dave Smith was secretary. Daniel Boone Chorus member Jerry Coen served on the festival committee.[49] The chorus finished eleventh in the Central States District Chorus Competition in 1973.[50]

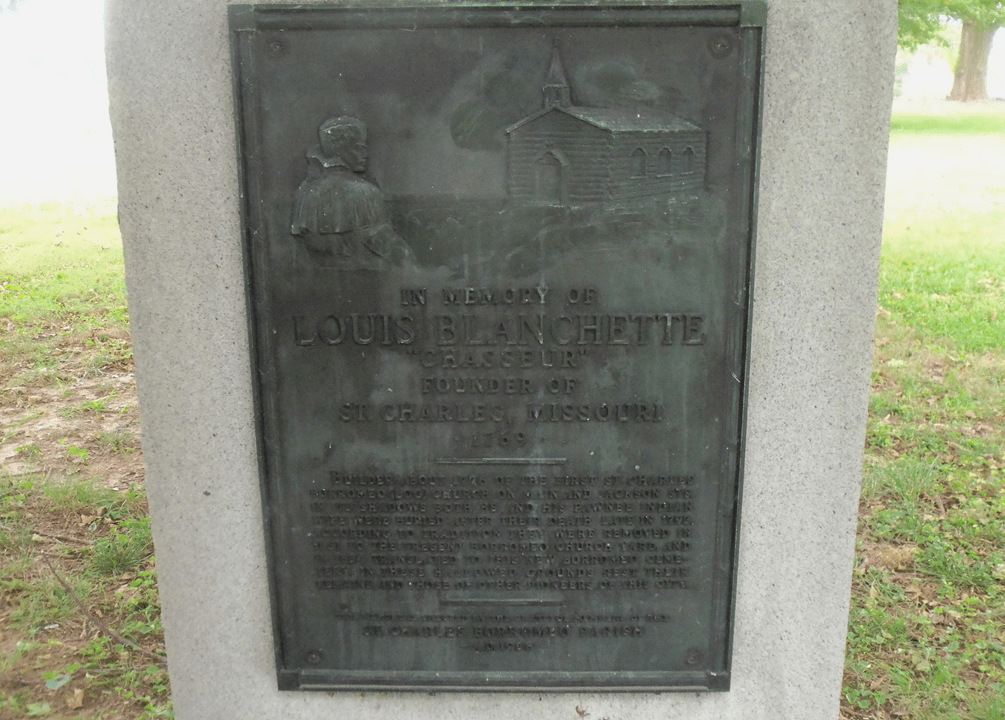

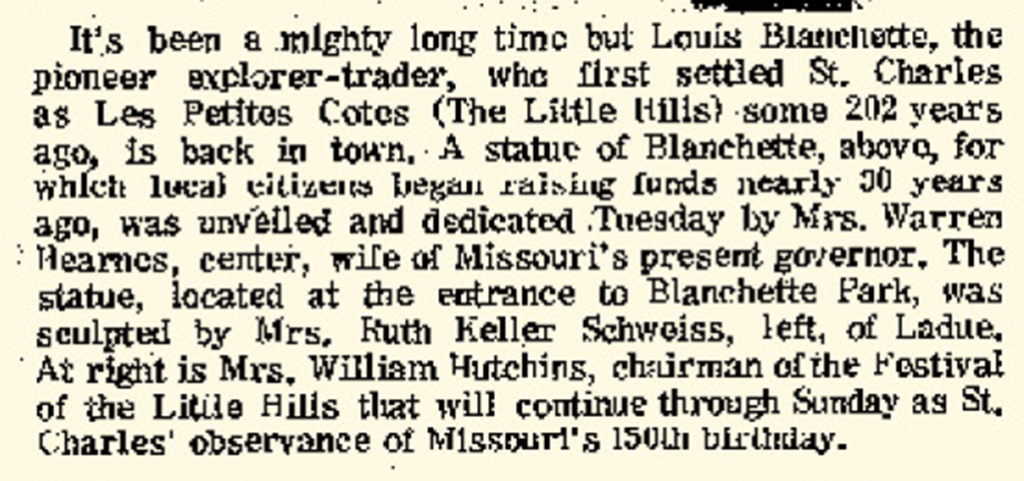

Shiz Hori was president in 1974. Hori joined the chapter in 1972. At the time, he was a resident of Hazelwood, Missouri, and worked for McDonnell Douglas.[51] The Daniel Boone Chorus traveled to Sioux Falls, South Dakota, the first week of May in 1974 to compete in the Central States District Preliminary Chorus Competition. The chorus finished in second place (981 points), only six points behind the winning chorus, the Shrine of Democracy Chorus from Rapid City-Mount Rushmore, South Dakota (987 points). The annual Spring Show was presented at St. Charles High School on 17 and 18 May at 8 p.m. with a dance to follow the Saturday night (17 May) performance at Blanchette Park. The shows had a circus theme and a river theme based on Mark Twain. The chorus planned to host the annual Afterglow on the final night of the International Barbershop Convention in Kansas City. The Afterglow was in the grand ballroom of the Muehlebach Hotel.[52]

The chorus performed at the Children’s Theatre in the St. Louis Art Museum on 15 June 1974.[53] The Daniel Boone Chorus performed in August 1974 at the Festival of the Little Hills.[54] Don Nevins left the chorus and the country in October 1974 and was succeeded as director by Joe Richardson.[55] Richardson was the only director to use a baton in his direction.[56] The resignation of Nevins as director sent the chapter into turmoil. Many of the old members left shortly after Nevins did, but many new members joined under the new director.[57] Richard L. “Rich” Knight, a high school teacher in the Fort Zumwalt School District, joined the Daniel Boone Chorus in 1974. Knight had previously sung with the Cosmopolitan Singers and appeared on the stage of the St. Louis Municipal Opera (the Muny).[58] Knight later gained international notoriety in the barbershop music world as the lead of the Gas House Gang quartet.

Ron Grooters was Chapter President in 1975. Ron and his wife Betty were married on 30 September 1961 in Yellowstone County, Montana.[59] He and his wife moved to St. Louis from Billings, Montana.[60] He sang bass with the Mutual Funs in 1971 at the St. Louis Muny’s production of “The Music Man.” Other quartet members were Bob Henry, Bert Volker, and John Jewell.[61] The following year, Jewell was replaced by Gordon Manion and the quartet was renamed the Gaslight Squires.[62] Grooters joined S.P.E.B.S.Q.S.A. in 1969 as a member of the St. Louis #1 Chapter. While a member of that chapter, he was their Assistant Secretary and Sergeant at Arms.[63] He was one of two contacts for men interested in auditioning for the St. Louis #1 Chapter in 1971.[64] Grooters joined the St. Charles chapter in 1972 and sang with the Daniel Boone Chorus and, later, the Ambassadors of Harmony until 2020. He taught Industrial Arts at Oakville Junior High School and lived in Mehlville, Missouri.[65] Grooters was later involved in two other quartets, Rivertown Sound and E-Male (1999-2000).[66] He was director of community education and extended services when he became assistant principal of Mehlville High School.[67] Jim Henry wrote a letter petitioning the chapter to join as an eleven-year-old in 1975.[68] The result was a change in the chapter rules allowing members under the age of sixteen if their father was already a chapter member.[69] At the time Jim joined the chorus, attendance averaged about twenty-five men who rehearsed sitting down. His father, Robert “Bob” Henry was already a member of the chorus and a member of the Gaslight Squires barbershop quartet.[70] Auditions in 1975 were held at Old Tyme Barbershop at 501 S. Fifth St. in St. Charles.[71] On 1 March 1975, the chorus performed a mini-show along with barbershop quartets and a dinner dance at St. Charles Borromeo Catholic Church at Fifth and Decatur streets.[72] On 13 September 1975, the chorus hosted the ninth annual St. Louis Area Barbershop Chorus and Quartet Contest at Ladue High School. The chorus finished fourth in the chorus competition and a quartet, the Gaslight Squires, from the chorus finished third in the quartet contest.[73] Other performances included singing in churches on Sunday mornings and an 27 August “sing-out” at Emmaus Home on Randolph Street.[74] The chorus added five new members in early October 1975: Marvin Boles (1924-1999), Knowles Dougherty (1934-2016), Harlan Ebeling (1923-2017), the aforementioned James Henry, and Bob Porchey (1937-2014).[75] Jim Henry served in several roles until becoming director of the Daniel Boone Chorus in 1990. He continued in that role until 2013, when he became co-director. The chorus performed, alternating with the Ladue High School Chorus, on 10 December 1975 at Plaza Frontenac. Both choruses shared the same director, Joe Richardson.[76] The Daniel Boone Chorus finished in ninth place in the Central States District Chorus Contest.[77]

In January 1976, the Daniel Boone Chorus performed at the 59th annual installation banquet of the St. Charles Chamber of Commerce at Stegton Ballroom.[78] Joe Richardson left the position of chorus director. Bob Henry and Gordon Manion co-directed the Daniel Boone Chorus from January to October 1976.[79] Bert Volker also helped in directing the chorus.

Larry Bloebaum was Chapter President in 1976.[80] A native of Mokane, Missouri, Bloebaum moved to Florissant and was employed by McDonnell Douglas.[81] He joined the St. Charles Chapter in the spring of 1973. He was elected Board Treasurer in 1974. The chapter board decided to have the chorus present “Bicentennial Revue.” The show produced positive results and new members joined the chorus.[82] Bloebaum later moved to Jefferson City, Missouri, but continues as an off-risers member of the St. Charles Chapter.[83] Twelve men auditioned for the chorus on 26 May 1976.[84] On 20 June 1976, the chorus performed at Six Flags over Mid-America.[85] In August 1976, the chorus took over the First State Capitol parking lot during the Festival of the Little Hills and scheduled a variety of entertainment, including the locally renowned Patt Holt Singers.[86] From October 1976 to October 1979, Bob Henry was sole director of the Daniel Boone Chorus.[87] During that time, he also directed the O’Fallon (MO) Chapter of the Sweet Adelines.[88] On 10 November 1976, the Daniel Boone Chorus held a guest night.[89]

The chapter president in 1977 was Dick Chambers. He joined the S.P.E.B.S.Q.S.A. and the St. Charles chapter in 1973. Chambers was chapter secretary in 1974. He donated video equipment to the chorus and sang in the Sound Effects Quartet. His work transferred him to Wichita, Kansas and there became active in the Wichita Capital Chorus. He returned to St. Louis in 1976 and then rejoined the chapter. At the time he was employed by McDonnell Douglas and living in Florissant, Missouri.[90] In 1977, the chorus changed rehearsal venues from St. John’s United Church of Christ to the St. Charles Presbyterian Church Hall.[91] The chorus also changed meeting nights from Wednesdays to Tuesdays.[92] In February, the chapter published an advertisement promoting “The recruitment of bathtub baritones, traffic jam tenors, barroom basses, and lonesome leads for the perpetuation of the barbershop sound.”[93] On 10 September 1977, the Daniel Boone Chorus finished second in the St. Louis Area Barbershop Competition at Ladue High School in Ladue, Missouri.[94]

Gary Goldman was Board President in 1978.[95] Gary Steven Goldman was born 3 June 1952 and died on 18 November 2017 in Phoenix, Arizona.[96] In 1978, the chorus performed at the Blues-Canadiens NHL game in St. Louis.[97] From 1979 to 1980, Lynn E. Bultman served as board president.[98] Bultman is a native of Indiana. He married on 15 October 1966 in Sunman, Indiana, to Janice Lee Klusman.[99] He was serving with the Seabees in the United States Navy in 1968.[100] In 1973, He became the manager of Indiana Cities Water Corporation in Newburgh, Indiana.[101] Lynn and his wife Janice were living in St. Joseph, Missouri, in 1975.[102] A veteran of the United States Navy, Bultman moved to St. Charles in 1976. He joined the St. Charles Chapter of S.P.E.B.S.Q.S.A. in 1977.[103] He was invited to the chorus by Gary Goldman. Bultman had a background in administration and helped in structuring policies and financial programs for the chapter. He laid the groundwork for financial stability so that the chapter could meet the needs of a growing organization while keeping in place reserves for future requirements.[104] Bultman was vice-president and general manager of Missouri Cities, a local water company, in 1986.[105] On 28 April 1979, the Daniel Boone Chorus finished second in the Central States District Chorus Prelims in St. Joseph, Missouri.[106] The chorus performed at the Festival of the Little Hills on 17 and 18 August 1979.[107] In the Fall Central States District Chorus Competition in Omaha, Nebraska, on 6 October 1979, the Daniel Boone Chorus finished eleventh out of sixteen competitors.[108] Shortly after that district, Bob Henry stepped down from directing and was succeeded by Gene Johnson, who directed the chorus until April 1981.[109] Under Johnson’s leadership, the Daniel Boone Chorus began participating in Christmas caroling on Main Street in St. Charles in December 1979.[110]

[1] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[2] The Coonskin Cappers Weekly VII, no. 1 (January 1970), Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[3] Proclamation signed by Henry C. Vogt on S.P.E.B.S.Q.S.A. letterhead, 1 April 1970, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives; St. Charles Daily Banner-News, April 1970, newspaper clipping in Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[4] Jerry Coen to Members of our St. Charles Chapter of S.P.E.B.S.Q.S.A., June 1970, followed by pictures of the show; St. Charles Cinema was located on Second Street until it was torn down in 1974 (see St. Charles Journal, 18 March 1974, Newspaper Archive, accessed 28 July 2020).

[5] Pictures dated 11 June 1970, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[6] Poster advertising event, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[7] Pictures in Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[8] St. Charles Journal, 8 October 1970, Newspaper Archive

[9] St. Charles Journal, 28 February 1972, Newspaper Archive

[10] “Chorus Wins Best Trophy,” St. Charles Daily Banner-News, 28 January 1971, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[11] CSD Chorus Contest Official Scoring Summary, Davenport, Iowa, 17 October 1970, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[12] Letter from Shirley White to S.P.E.B.S.Q.S.A., 5 October 1970, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[13] Program, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

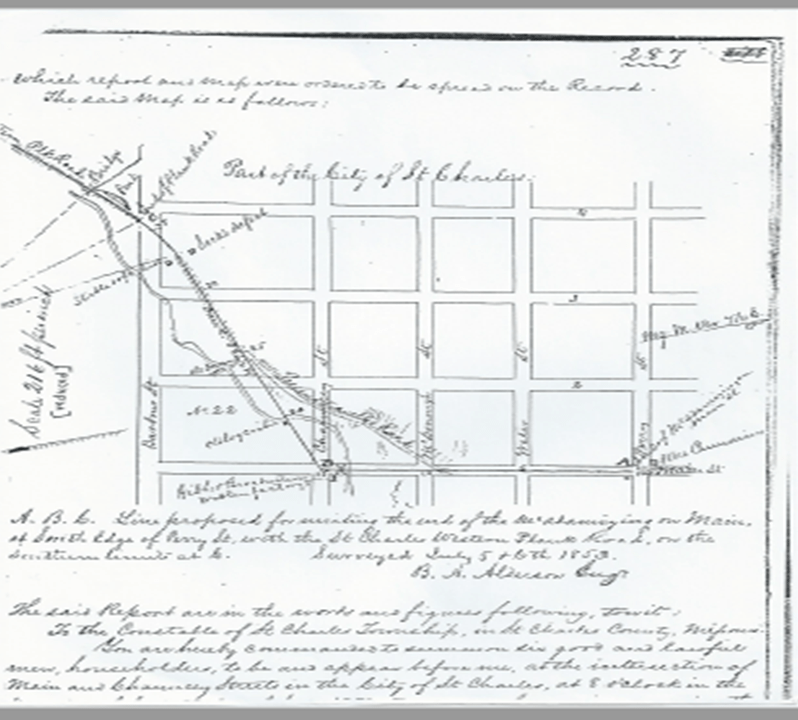

[14] Map, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[15] St. Charles Daily Banner-News, December 1970, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[16] This is the nickname given it by local historian Edna McElhiney Olson, but the story does not appear to be correct. The building at 500 S. Main St. appears to have originally been a warehouse for Francis X. Kremer’s mill (as seen on the 1869 Bird’s Eye View of St. Charles). The building sustained damage in the 1876 tornado and appears to have been redone in its current configuration shortly after that tornado.

[17] St. Charles Journal, 21 January 1971, Newspaper Archive

[18] St. Charles Daily Banner-News, 21 January 1971, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[19] A chain of command for 1971 is in Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[20] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[21] Newspaper clipping, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[22] St. Charles Journal, 18 February 1971, Newspaper Archive; Karen Tuttle, “Wife sees good in husband’s surgery,” St. Charles Daily Banner-News, 22 February 1971, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[23] Information card and program, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[24] “St. Charles Moving Ahead,” Gerry Mohr, 3 August 1971, report in Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[25] St. Charles Journal, 15 April 1971, Newspaper Archive; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, 6 April 1971, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives; pictures of this performance are also in the binder; Another article advertising this is in the Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1971-79

[26] Mohr in Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[27] St. Charles Daily Banner-News, 23 July 1971, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives; the program, a review by Frank Hunter of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, a congrats to the quartet by Bob Goddard in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Wednesday, 21 July 1971; Myles Standish, “’Music Man’ Opens at Municipal Opera,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 27 July 1971, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1971-79, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[28] St. Charles County Historical Society Photo 12.1.087, image accessed 6 July 2020

[29] Program, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[30] Official Scoring Summary, 2 October 1971, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[31] Note card listing directors and rehearsal venues, Ambassadors of Harmony archive

[32] St. Charles Journal, 2 December 1971, Newspaper Archive

[33] https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/153532801, accessed 20 July 2020; birthplace surmised from family’s residence in St. Louis in the 1940 U.S. Census

[34] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[35] St. Charles Journal, 14 February 1972, Newspaper Archive

[36] “Barbershop Singers Schedule Auditions for New talent,” St. Charles Journal, 28 February 1972, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1971-79, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[37] St. Charles Journal, 28 February 1972, Newspaper Archive

[38] St. Charles Journal, 12 June 1972, Newspaper Archive

[39] St. Charles Journal, 24 August 1972, Newspaper Archive

[40] Esther Talbot Fenning, “Festival of the Little Hills – Cooks Again on Riverfront,” St. Charles Post, 10 August 1995

[41] St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 23 August 1972, Newspapers.com; http://www.preservationjournal.org/public/FrontierPark/Frontier.html, accessed 7 July 2020

[42] St. Charles Journal, 25 September 1972, Newspaper Archive

[43] Gerry Mohr, “St. Charles Enjoys,” December 1972, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1971-79, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[44] St. Charles Journal, 9 November 1972, Newspaper Archive

[45] St. Charles Journal, 7 December 1972, Newspaper Archive

[46] http://www.barbershopwiki.com/wiki/Ambassadors_of_Harmony, accessed 6 July 2020; St. Charles Journal, 19 October 1972, Newspaper Archive

[47] St. Charles Journal, 5 March 1973, Newspaper Archive

[48] St. Charles Journal, 26 February 1973, Newspaper Archive

[49] St. Charles Journal, 18 October 1973, Newspaper Archive

[50] https://www.barbershopwiki.com/wiki/Ambassadors_of_Harmony, accessed 7 July 2020

[51] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[52] St. Charles Journal, 9 May 1974, Newspaper Archive

[53] St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 14 June 1974, Newspapers.com

[54] St. Charles Journal, 21 August 1974, Newspaper Archive

[55] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archive

[56] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archive

[57] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archive

[58] Newspaper clipping, Daniel Boone Chorus binder, 1970-71, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[59] Montana Marriage Records, 1943-1988, www.ancestry.com, accessed 20 July 2020

[60] He and his wife are listed as parents in Montana Birth Records, 1897-1988, www.ancestry.com, accessed 20 July 2020

[61] “In Muny’s Music Man,” St. Charles Journal, 26 July 1971, Newspaper Archive, accessed 20 July 2020

[62] “Award-Winning Squires,” St. Charles Journal, 19 October 1972, Newspaper Archive, accessed 20 July 2020

[63] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archive

[64] Want ad placed by St. Louis No. 1 Chapter of the Society for the Preservation and Encouragement of Barber Shop Quartet Singing in America, Inc. in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 14 November 1971, Newspapers.com, accessed 20 July 2020

[65] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[66] Members.barbershop.org, accessed 20 July 2020

[67] “Changes,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Newspapers.com, accessed 20 July 2020

[68] Joel Currier and Michael Kunz, “The Biggest Man in Barbershop,” The Harmonizer (May/June 2010), 18

[69] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archive

[70] http://harmonyuniversity.blogspot.com/2007/08/gold-medal-moments-by-dr.html, accessed 7 July 2020; St. Charles Journal, 31 July 1975, Newspaper Archive

[71] St. Charles Journal, 12 March 1975, Newspaper Archive

[72] St. Charles Journal, 28 February 1975, Newspaper Archive

[73] St. Charles Journal, 1 October 1975, Newspaper Archive

[74] St. Charles Journal, 24 September 1975, Newspaper Archive

[75] St. Charles Journal, 8 October 1975, Newspaper Archive

[76] St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 9 December 1975, Newspapers.com, accessed 16 December 2019

[77] http://www.barbershopwiki.com/wiki/Ambassadors_of_Harmony, accessed 7 July 2020

[78] St. Charles Journal, 19 January 1976, Newspaper Archive

[79] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archive

[80] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archive

[81] 1940 U.S. Census, www.ancestry.com, accessed 20 July 2020

[82] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archive

[83] Members.barbershop.org, accessed 20 July 2020

[84] St. Charles Journal, 16 June 1976, Newspaper Archive

[85] St. Charles Journal, 28 June 1976, Newspaper Archive

[86] St. Charles Journal, 19 August 1976, Newspaper Archive

[87] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archive

[88] Troy Free Press and Silex Index (MO), 10 May 1978, Newspaper Archive

[89] St. Charles Journal, 10 November 1976, Newspaper Archive

[90] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archive

[91] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archive

[92] St. Charles Journal, 24 February 1977, Newspaper Archive

[93] St. Charles Journal, 23 February 1977, Newspaper Archive

[94] St. Charles Journal, 15 September 1977, Newspaper Archive

[95] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archive

[96] Obituary, St. Louis Jewish Light, 29 November 2017, Newspapers.com, accessed 20 July 2020

[97] St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 8 February 1988, Newspapers.com, accessed 22 November 2018

[98] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archive

[99] Indiana Marriage Certificates, 1960-2005, www.ancestry.com, accessed 20 July 2020

[100] Greensburg (IN) Daily News, 18 April 1968, Newspaper Archive, accessed 20 July 2020

[101] Newburgh (IN) Register, 6 September 1973, Newspapers.com, accessed 20 July 2020

[102] Greensburg (IN) Daily News, 11 December 1975, Newspaper Archive, accessed 20 July 2020

[103] “Barbershop Group Adds New Member,” St. Charles Journal, 7 April 1977, Newspaper Archive, accessed 20 July 2020

[104] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archive

[105] St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 11 March 1986, Newspapers.com, accessed 21 July 2020

[106] 1979 Central States District scores, which were available online in 2017, but not in 2020

[107] St. Charles Journal, 16 August 1979, on microfilm at Kathryn Linnemann Branch, St. Charles City-County Library District

[108] 1979 Central States District scores, which were available online in 2017, but not in 2020

[109] Index card, Ambassadors of Harmony archives

[110] “Christmas on St. Charles’ Main Street,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 30 November 1981, Newspapers.com, originally clipped by David Revelle, 17 September 2016