NOTE: The below narrative reflects the various versions of the article that appeared in the St. Charles County Heritage in April 2019. A huge help in the research process was the previous writeup on Blanchet done by Mitzi Riddler (now Mitzi Smith). There is some additional information below that I took out for the sake of length. I also have found some additional items of interest since writing the article. Some of the items I discuss here I found independent of the research of Maureen Rogers-Bouxsein for Rory Riddler, For King, Cross, and Country, which was in publication at the same time I did the below research. Although none of the below is based on her research, I wanted to acknowledge the work she did in researching Louis Blanchet for Riddler’s 2019 book. Some authors drop the “s” off of “Petites” for the town name, but that violates typical French pluralization rules, in which a plural noun pluralizes all preceding modifiers. More recent research of Ben Gall of the St. Charles County Heritage Museum and additional research by me has led to a new update in 2024. I have included information from Riddler’s book in this new update. – Justin Watkins

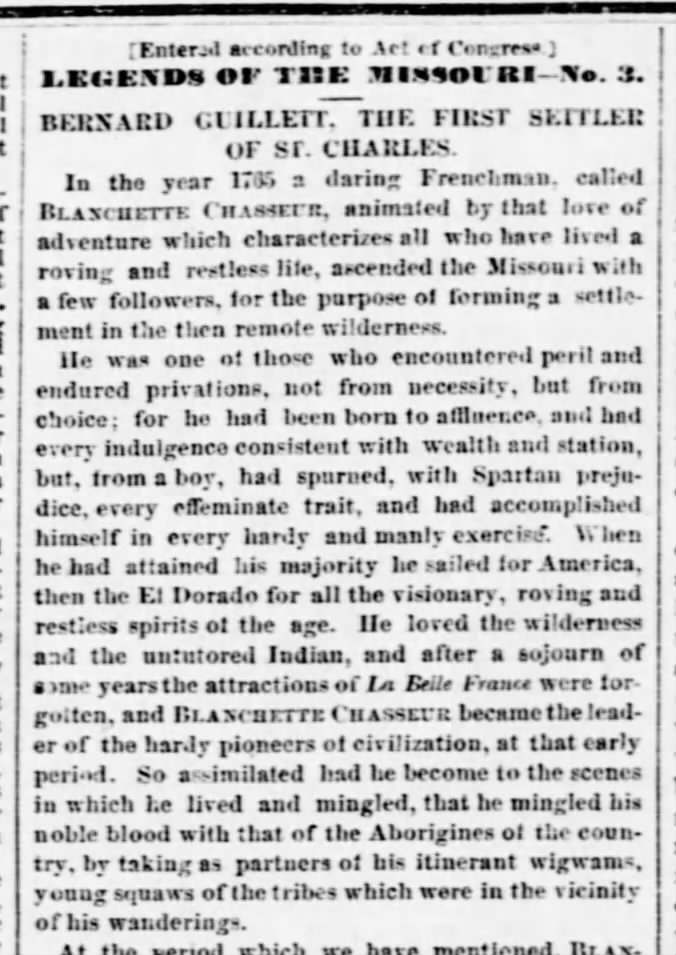

It was a wilderness filled with trees. Nearby ran the muddy, murky water of the Missouri River. The river often contained snags that could sink any boat at any time yet, for one French Canadian and his friends, it proved to be the gateway to new adventure and a new settlement. According to Dr. Menra Hopewell, Blanchette and his three friends encountered one Bernard Guillet at this site in October 1765.[1] The source of Hopewell’s information about Bernard Guillet and Louis Blanchette is unknown, but the story has been repeated often in subsequent published histories of St. Charles and St. Charles County. Hopewell was a medical doctor who wrote several works of history which have since been regarded as suspect. The story of Bernard Guillet and Louis Blanchet is one of the legends that Hopewell shared in Legends of the Missouri and Mississippi.

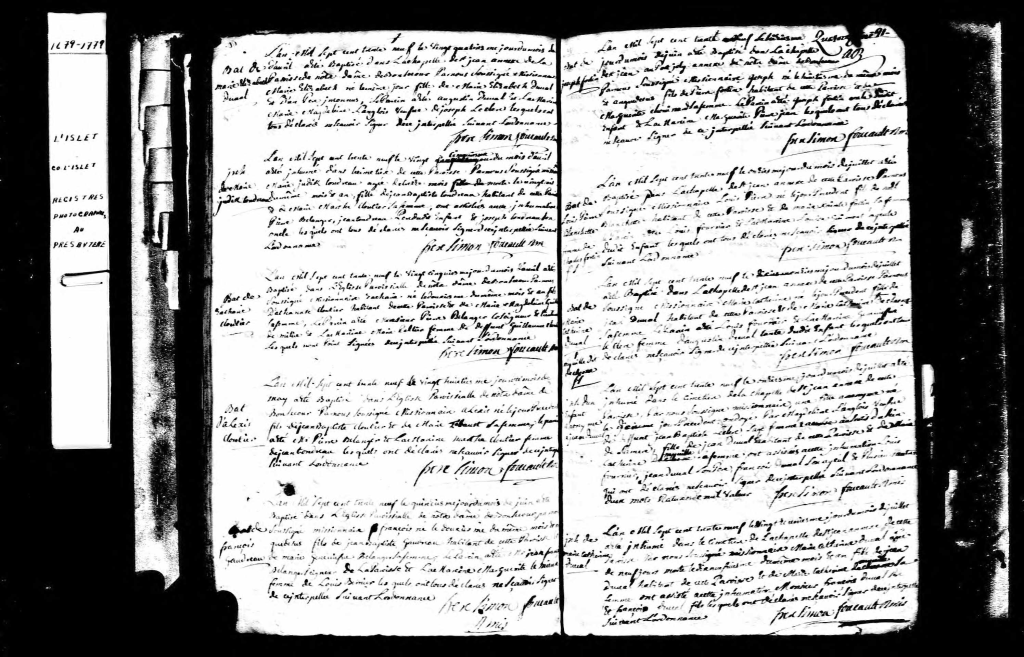

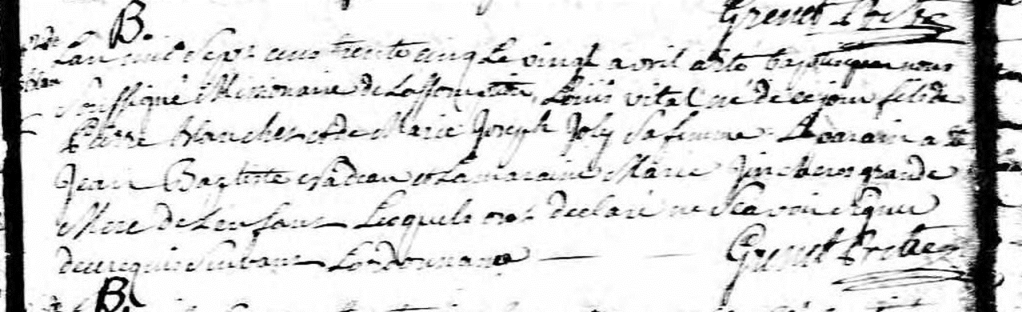

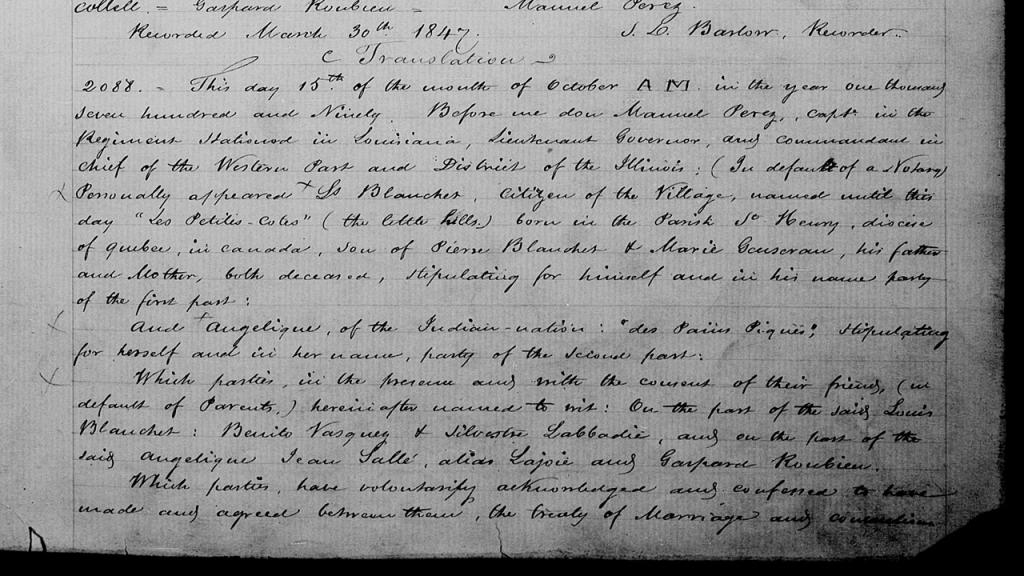

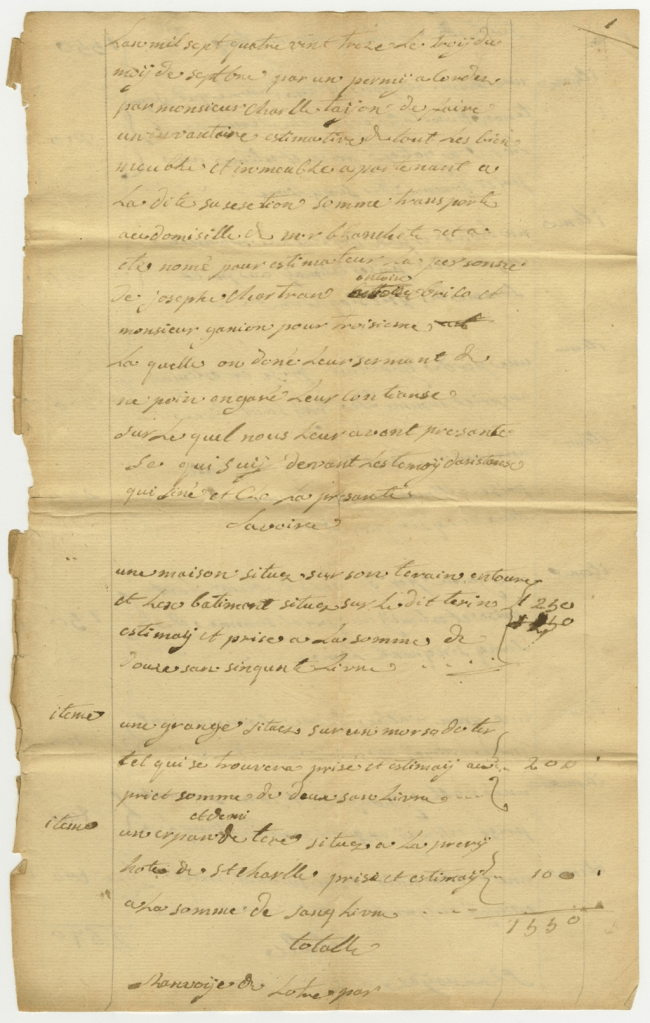

According to Hopewell, Blanchet had grown up in a wealthy family, but his love of adventure and daring caused him to leave comfort and fortune behind and adopt the life of an explorer and hunter. It was a dangerous, hard life to live, but Blanchet loved it. Hopewell incorrectly states that Blanchet was from France. Many online sources (and Riddler 35) claim that Blanchet is the same as Louis-Pierre Blanchet, who was baptized on 11 July 1739 in L’Islet sur Mer, Quebec, Canada. He was born to Noël and Marie (Saint-Fortin) Blanchet.[2] The main source for this information is Godfrey Blanchet’s Livre-souvenir de la Famille Blanchet (Souvenir Book of the Blanchet Family), published in 1946 (a copy of this book is at the St. Charles County Historical Society; see also Riddler 35). Louis Houck, in his A History of Missouri, claimed that Louis Blanchette’s parents were Pierre Blanchette and Mary Gensereau (Houck, A History of Missouri II: 80). Contemporary records lead me to lean toward the parents identified by Houck (which was taken from the 1790 marriage record and not from Father Cyprien Tanguay as claimed in Riddler 35). The parents given for Louis-Pierre Blanchette do not match those given by the Louis Blanchet who married “Angelique” in 1790. The below image is of the baptismal record for Louis-Pierre Blanchette, which lists his parents as Noël and Marie (Saint-Fortin) Blanchette.

Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours, L’Islet-sur-Mer, Quebec, Canada

Drouin Collection, accessed via Ancestry Library, 30 March 2020

Louis Pierre, born the day before, son of Noel Blanchette, inhabitant of the said parish and Marie Xainte Fortin, his wife, of the parish”

Image 790, Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours, L’Islet, Quebec, Canada

Quebec Catholic Parish Registers, 1621-1979

“Québec, registres paroissiaux catholiques, 1621-1979.” Database with images. FamilySearch. https://FamilySearch.org : 21 March 2020. Archives Nationales du Quebec (National Archives of Quebec), Montreal. FHL Film # 005459923

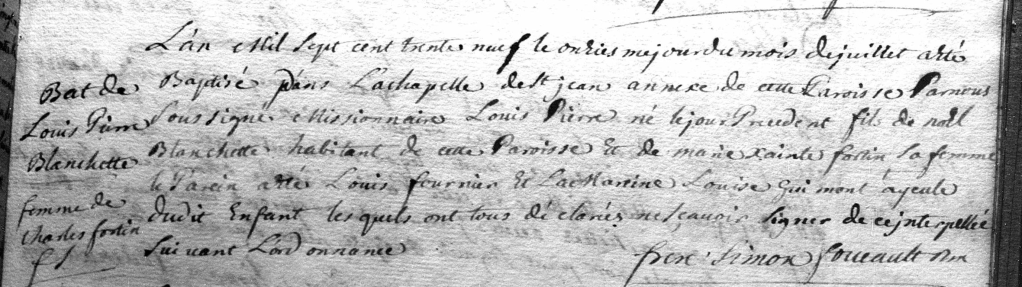

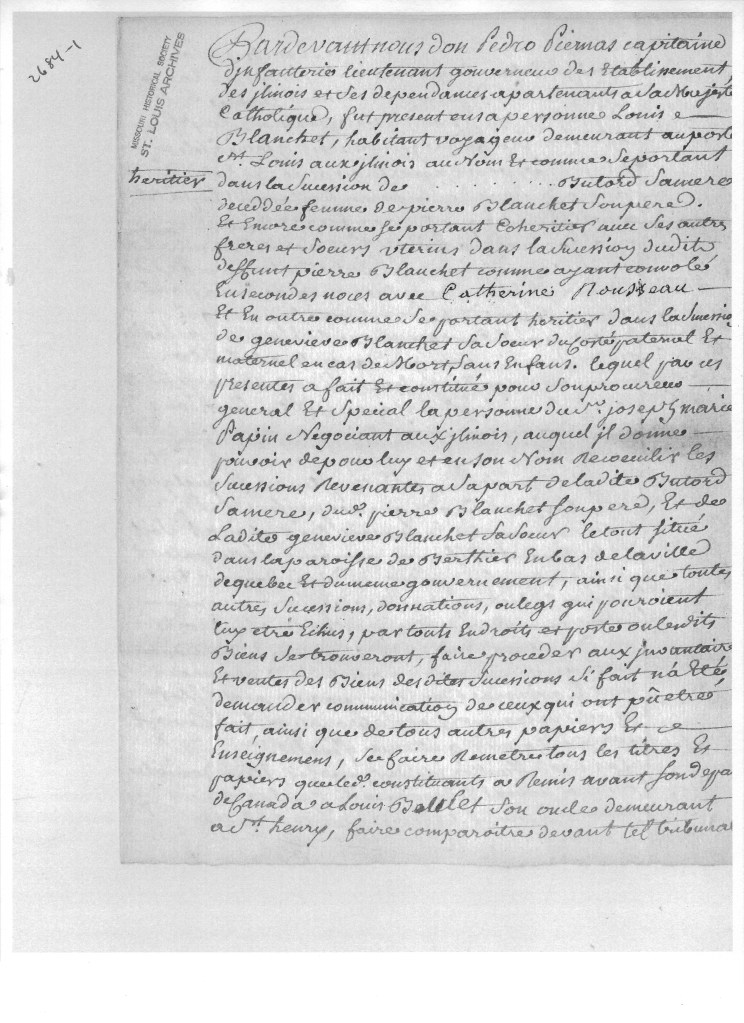

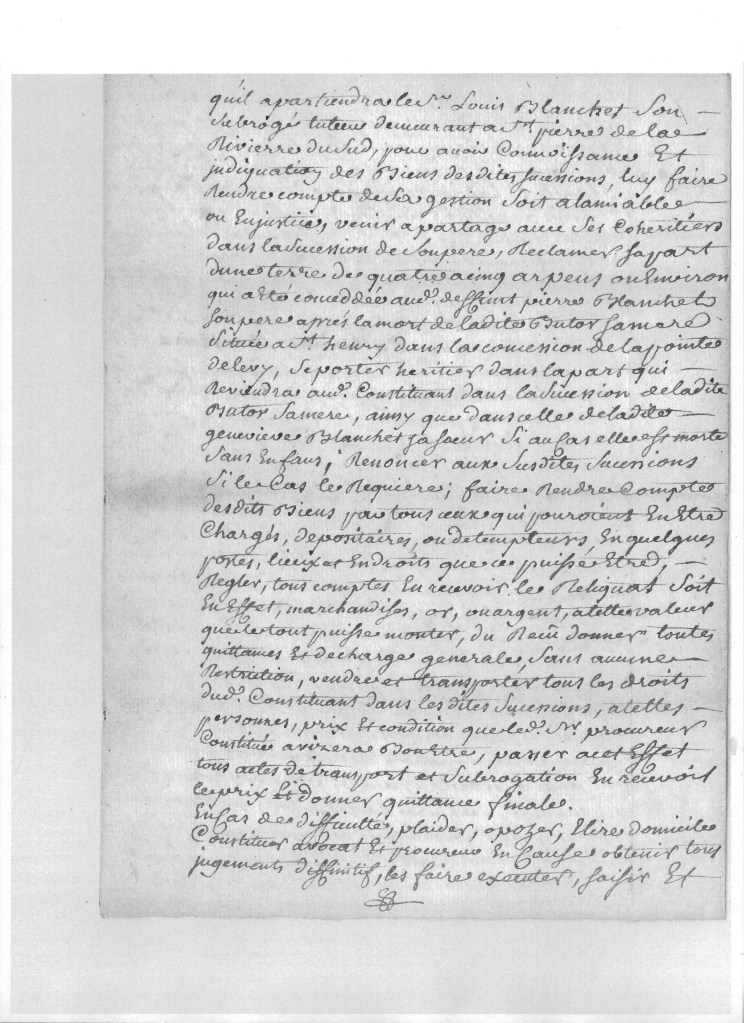

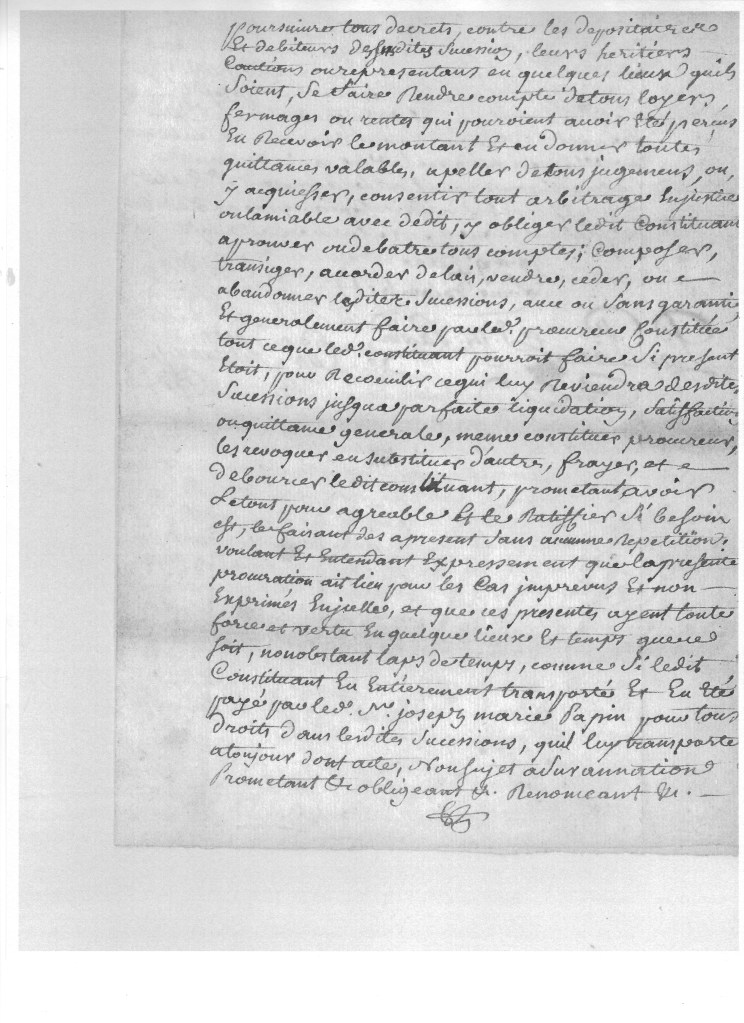

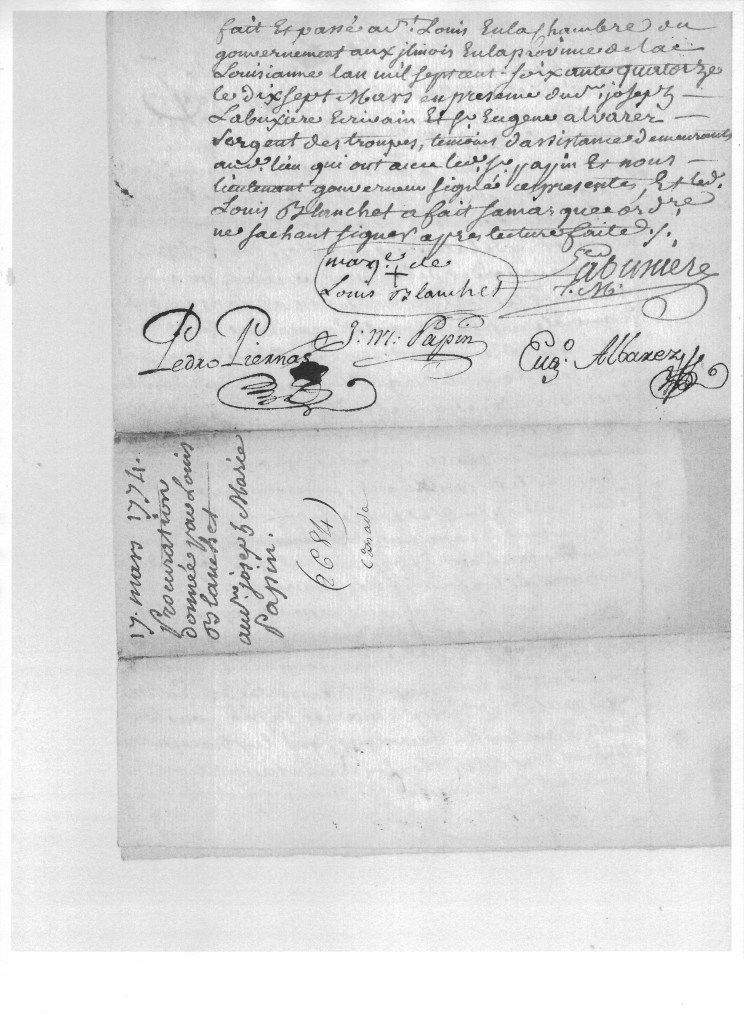

The marriage record of Blanchette and information given in St. Louis Archives document no. 2684 (this document was mentioned in Mitzi Smith’s writeup on Blanchet for the South Main Preservation Society) tend to give credence to his real name being Louis-Vital Blanchet, son of Pierre and Marie Joseph (Jolly) Blanchet, who was baptized on 20 April 1735 in Berthier-sur-Mer Parish, Quebec, Canada. The lineage given by Riddler in For King, Cross, and Country (Riddler 35-36) is still correct down to the grandfather’s generation. Louis-Vital Blanchet was a first cousin of Louis-Pierre Blanchette, their fathers both sharing the same parents (https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Blanchet-157 and https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Blanchet-41). Louis-Vital Blanchet’s father Pierre married (2) Catherine Rousseau, which matches the information in St. Louis Archives document no. 2684. Louis-Vital Blanchet had several siblings, including sisters named Catherine and Genevieve, both of which are named as his sisters in St. Louis Archives document no. 2684. The document deals with a power of attorney in which he is divesting himself of property in which he has an interest in Berthier-sur-Mer, Quebec, Canada in 1774 (see later for the images of this document, taken from a copy made for the author during his visit to the Missouri Historical Society on 7 May 2024).

At the time of Blanchet’s birth, waterways were the routes of travel and Blanchet moved down the St. Lawrence River Valley into what was then known as Illinois Country. By the time of Blanchet’s birth, the French had penetrated the heart of the North American continent and explored parts of the Mississippi and Missouri River valleys. The Mississippi River, first discovered in 1541 by Hernando de Soto, provided an inland water route accessed from the south via its delta near New Orleans, Louisiana.[3] The turbulent confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers was first experienced by French explorers Louis Joliet and Father Jacques Marquette in June 1673. This was the first time Europeans saw the Missouri River.[4]

In the eighteenth century, French settlers began founding settlements on the Mississippi River, beginning with Sainte Genevieve in 1735.[5] Further settlement did not occur west of the Mississippi until after 1763. With the French in control of Canada, there was no need to move further west unless one was a hunter in search of new hunting grounds. The story told by Hopewell indicates that Bernard Guillet, a Frenchman, became a hunter in search of new hunting grounds. According to the somewhat apocryphal story, Guillet was born near Marseilles and was orphaned at the age of eleven. (A search for Guillet as a surname turned up a number of results on Ancestry). He was apprenticed to a tanner, who mistreated Guillet. “I was worked hard and almost starved,” he later recalled. At the age of seventeen, Guillet was still working for the tanner, when the tanner snatched away the rosary Guillet’s mother had given him. Guillet asked for it back, but his boss insulted Guillet’s late mother. The insult drove Guillet into a murderous rage. Guillet fled for the New World and apprenticed as a sailor. After three months he arrived in North America and continued into the interior of the continent as a vagabond. Guillet eventually wound up on the site of St. Charles and lived there for several months. He trapped beaver and muskrats with much success until he discovered that an Indian was stealing from the traps. He shot and killed the Indian, but the death was discovered by some of the Indian’s friends. A band of Dakota Indians captured Guillet in retaliation for the death of the Indian and carried him off to their tribal council. Guillet was sentenced to death, but one of the Dakota women claimed him as her husband. Guillet was safe and soon became part of the tribe. He eventually married the chief’s daughter and succeeded the chief upon the chief’s death. So goes the story as told by Hopewell.[6]

Most hunters did not have such wild tales to share. Their adventures in finding new hunting grounds were often punctuated by wars between the English and French colonists. For example, the French and Indian War from 1754 to 1763. With the signing of the Treaty of Fontainebleau in 1762, Louisiana came under Spanish jurisdiction, while French Canada became part of the British Empire in the 1763 Treaty of Paris.[7] With the British came the Anglican Church and certain aspects of Catholicism were discouraged. The Catholic Encyclopedia reports, “The communities of men, Recollects, Jesuits, and Sulpicians, were forbidden to take novices in Canada, or to receive members from abroad. They were marked out for extinction, and the State declared itself heir to their property. The English confiscated the goods of the Recollects and Jesuits in 1774, and granted the religious modest pensions.”[8] Jesuits in Illinois were expelled from Illinois at the end of the French and Indian War.[9] The Jesuits were suppressed by Pope Clement XIV in 1773 and were not restored as a society until 1814 under Pope Pius VII.[10] The religious factor was not the only one to play a role in the westward migration of some French Canadians to Louisiana. For the French traders to continue to deal with the Indians, they needed to remain close enough to continue the trade network.

Surprisingly, the next Louisiana Territory settlement was not founded by French Canadians or francophone Illinois settlers, but by two men who made the trek north from New Orleans. St. Louis, named after King Louis IX of France, is widely regarded as founded by Pierre Laclede and Auguste Chouteau in 1764. In 2016, Dr. Carl Ekberg and Dr. Sharon Person raised questions as to the date of the founding of St. Louis and as to whether Laclede and Chouteau really founded the town. Ekberg and Person concluded that Laclede and Chouteau probably did not found the town in 1764 as claimed in Chouteau’s journal. They decided that the village of St. Louis gradually developed over time as francophone settlers from Illinois spilled across the Mississippi River to St. Louis. The earliest census for St. Louis was in 1766.[11]

By the time St. Louis was founded, Louis Blanchet had already been living in the area for quite some time. It has been suggested that Blanchet moved to an area near St. Louis as early as 1758.[12] Louis-Vital Blanchet was still in Canada in 1755, where we find him as a resident of St. Henri-de-Lauzon, fulfilling an obligation to pay $171.10 to Jean Dambourges (Quebec, Canada, Notarial Records, 1637-1935, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/142498:61062?tid=&pid=&queryId=694011cf-4a7b-435f-84ef-51f6aed690e0&_phsrc=Vvl1421&_phstart=successSource). Known as “le Chasseur,” (the hunter) Blanchet first arrived at the site of St. Charles in October 1765. Hopewell’s legend mentions that Blanchet came with three friends who were also hunters and trappers. Blanchette and his three companions were rowing up the swift current of the Missouri River when they saw several small hills in the distance. From one of the hills they saw smoke coming from a campfire. Blanchette, armed with a rifle, went ashore to investigate. It was a campsite of some Native Americans who were preparing supper. They looked up and spotted him. Blanchette quickly tied a white cloth to the end of his gun, signaling that he came in peace. He realized immediately who was the chief. It was the man wearing a rich display of beads and feathers. Two of Blanchette’s friends joined him, but the other (who was half-French, half-Indian) took off running. Once captured by the chief’s braves, the half-French, half-Indian was brought to the camp and the chief assured him that his scalp was as safe as the crown on the king of France. Blanchet and his companions spent the night with the chief, Bernard Guillet, and the braves. Guillet told Blanchet the story of how Guillet originally came from France and wound up as chief of the Dakotas. The next morning, Blanchette asked the chief if he had given a name to the place that had one been the chief’s home. Guillet replied, “Yes, I called it Les Petites Côtes because of the little hills you see.” Blanchette responded, “By that name it will be called for it is the echo of nature—beautiful from its simplicity.”[13]

John Roy Musick of Kirksville, Missouri (but a native of St. Louis) in his Stories of Missouri claims that Blanchette was “among the earliest settlers of St. Louis.” (John Roy Musick, Stories of Missouri, New York: American Book Company, 1897, 35) Musick writes that Blanchette was “a friend of Laclede and Chouteau” who “loved the forest and preferred hunting to cultivating the soil or trading with Indians; so, he came to be called ‘Blanchette Chasseur,’ or Blanchette the Hunter. He would spend days alone in the forest with his gun and dogs. On account of rattlesnakes and copperheads, which were abundant, he often climbed into the branches of a tree to sleep.

“Once, having chased a wounded deer until darkness came upon him, he looked about for a tree in which to pass the night. A large oak with thick clusters of branches and dense foliage seemed to invite him to repose in its bushy top. He climbed to the first fork and took the most comfortable position he could find. Hanging his rifle by a leather strap on a small branch at his side, he prepared to sleep.

“His faithful dogs, which had been following the deer, returned to their master shortly he was in his strange bed, and set up a tremendous howling. He spoke to them and ordered them away, but all to no purpose. They remained beneath the tree, barking furiously.

“‘Something is wrong,’ thought the hunter, ‘or those dogs would not act in this way.’

“He crept down the tree, and with his flint and steel kindled a fire. As the light ascended into the branches, he saw a pair of fiery eyes not ten feet from where he had been resting. The hunter raised his rifle, took aim, and fired. An enormous panther fell, mortally wounded. The dogs leaped on it, and though it was dying, it succeeded in killing one of them.

“Blanchette was not only a great marksman, but a great horseman as well, and many stories are told of his skill with horse and rifle. He was once hunting with an Indian friend when they started up a fine fat buck. The Indian fired and missed.

“‘Never mind; I will get it for you,’ said Blanchette; and he galloped away after the deer, which was running toward the river. When the animal reached the water’s edge, it turned north, whereupon the hunter cut across through the wood to head it off. He came out within a hundred paces of it, and horse and deer sped along neck and neck. Blanchette dropped the rein and, raising his rifle, brought down the deer at the first shot without slackening his speed. He gave it to his Indian friend, and an hour later had shot one for himself.” (Musick 35-38, reprinted in Riddler 33-34)

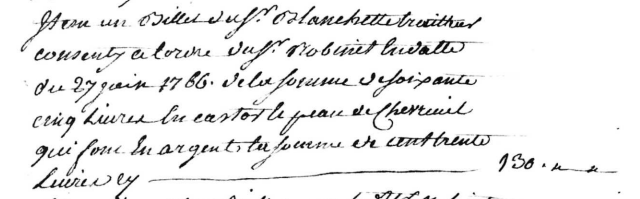

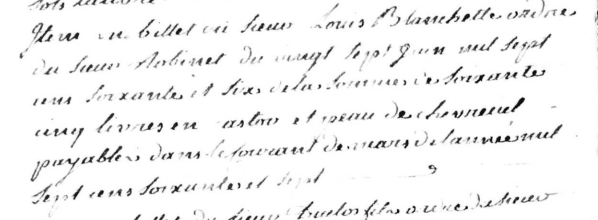

Although the veracity of the above stories cannot be verified, it can be shown that Louis Blanchet/Blanchette was in Ste. Genevieve, Missouri, in 1766. Louis Robinet’s estate in 1770 still owed money to Blanchet for a bill of $130 from 1766 (Ste. Genevieve, Missouri, Archives, State Historical Society of Missouri, Columbia, Collection C3636, f. 347; see also Ben Gall, “New exhibits at Heritage Museum explore Colonial St. Charles and the War of 1812,” St. Charles County Heritage, XL: no. 2 [April 2022], 64).

According to Musick, “In 1768, attracted by the abundant game north of the Missouri River, he [Blanchette] crossed that stream and built a log cabin. The advantages of hunting and trapping here were so superior to those south of the river, that he induced some friends to join him.” (Musick 38)

In April 1769, Blanchet returned with several other friends and family from Quebec and formed a village on the site where Blanchet and Guillet had met. True to his promise to Guillet, Blanchet named his new settlement Les Petites Côtes. It was located within the Louisiana Territory, which was owned by the Spanish. Louisiana had not always been owned by the Spanish. A series of conflicts, known as the French and Indian Wars, were fought between 1688 and 1763. Of these the last, the French and Indian War (or Seven Years’ War in Europe), was the only to start in North America and spread to Europe. France lost the war and began to make treaties. With the signing of the Treaty of Fontainebleau in 1762, Louisiana came under Spanish jurisdiction, while French Canada became part of the British Empire in the 1763 Treaty of Paris.[14] The new governor of Louisiana, Jean-Jacques d’Abbadie, did not receive word of the transfer from France to Spain until 1764.[15]

With the British came the Anglican Church and certain aspects of Catholicism were discouraged. The Catholic Encyclopedia reports, “The communities of men, Recollects, Jesuits, and Sulpicians, were forbidden to take novices in Canada, or to receive members from abroad. They were marked out for extinction, and the State declared itself heir to their property. The English confiscated the goods of the Recollects and Jesuits in 1774, and granted the religious modest pensions.”[16] Jesuits in Illinois were expelled from Illinois at the end of the French and Indian War.[17] The Jesuits were suppressed by Pope Clement XIV in 1773 and were not restored as a society until 1814 under Pope Pius VII.[18] The religious factor was not the only one to play a role in the westward migration of some French Canadians to Louisiana. For the French traders to continue to deal with the Indians, they needed to remain close enough to continue the trade network. This combination of economics and religion, affected by the outcome of the French and Indian War, led some French Canadians to head for newer territory west of the Mississippi River.

Settlement in present-day Missouri was slow to develop. Ste. Genevieve may have been founded as early as 1735 or as late as 1750, but no subsequent settlements were made until after the French and Indian War of 1754-1763. The first settlement established after that war was St. Louis, which reportedly was founded in 1764 by Pierre Laclede and Auguste Chouteau. St. Louis was named for King Louis IX of France, who was canonized by the Roman Catholic Church on 11 August 1297.[19] Although there is some question as to the veracity of Laclede and Chouteau founding St. Louis, the village existed as early as 1766, when a territorial census was taken.[20] In 1767, Carondelet was founded by Clément Delor de Treget.[21]

Blanchette established Les Petites Côtes on the west bank of the Missouri River.[22] Blanchette apparently was not alone when he arrived in 1769. In 1892, James Joseph Conway reported, “The city was founded by a Catholic colony of French trappers and hunters about 1769.”[23] One companion of Blanchette was Pierre LeFaivre, whose granddaughter, Euphrasie C. Yosti, married Henry Clay Easton.[24] According to Duane Meyer, “As in other French settlements, the inhabitants planted crops and grazed their animals in the large common fields surrounding the town. However, most settlers also engaged in hunting and the Indian trade.”[25] The new settlement was located in an area once inhabited by Native American Indians in the 15th century.[26] It was also visited by French explorers traveling west on the Missouri River to the mouth of the Kansas River in 1705.[27] Blanchette built a log cabin, one of three erected in Les Petites Côtes in 1769.[28] At the time, the area was “a series of beautifully symmetrical hills overlooking to the north a lovely stretch of plains bordering the great rivers and clothed in all the wealth of spring-time verdure and summer flowers. No natural landscape could have been more entrancing than the Missouri and Mississippi valley covered with green grass and wild flowers as tall as a man on horseback.”[29] Daniel Brown imagined Les Petites Côtes as “diminutive and nearly defenseless, the new settlement sat on a broad sweeping curve of the river, swaddled amongst a sea of variegated greens; of pine and oak, of sycamore and ash, of red cedar and shagbark hickory, of dogwood and redbud, and the yellow-green of prairie grass meadows. Leadplant, purple coneflower, Indian paintbrush, prairie phlox, and white wild indigo swept and swirled about small open savannahs. On the crest of the hills behind the settlement stood groves of linden, pin oak, sumac, white ash and hazelnut.”[30]

Microfilm collection, Local History and Genealogy Department

Headquarters Branch, St. Louis County Library

Frontenac, MO

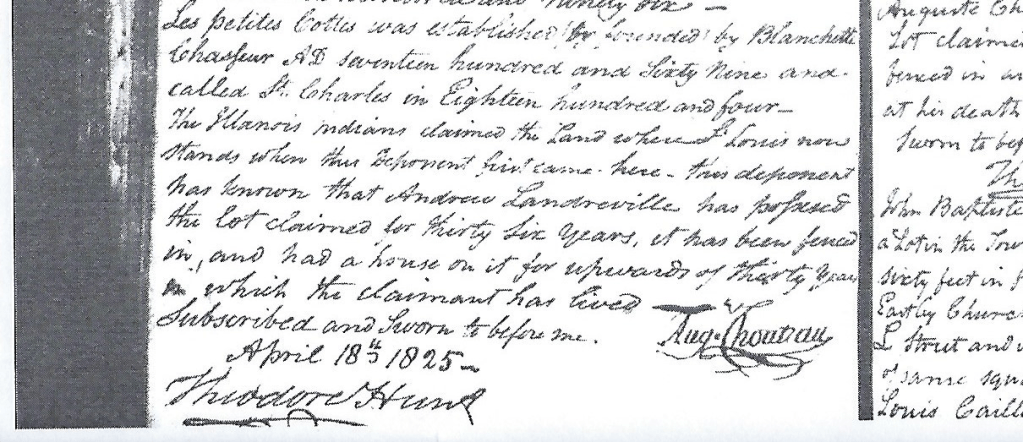

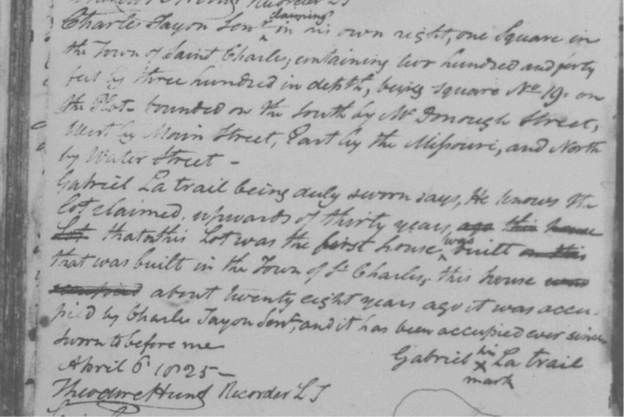

Blanchette picked a spot that later became identified on the town plat as Block 19 (800 block of S. Main), bordered by Water, McDonough, and Main streets and the Missouri River.[31] Gabriel Latrail testified in 1825 to Theodore Hunt, United States Recorder of Land Titles, that City Block 19 was where the first house was built in St. Charles.

Microfilm collection, Local History and Genealogy Department

Headquarters Branch, St. Louis County Library

Frontenac, MO

Photograph taken by Justin Watkins in September 2019

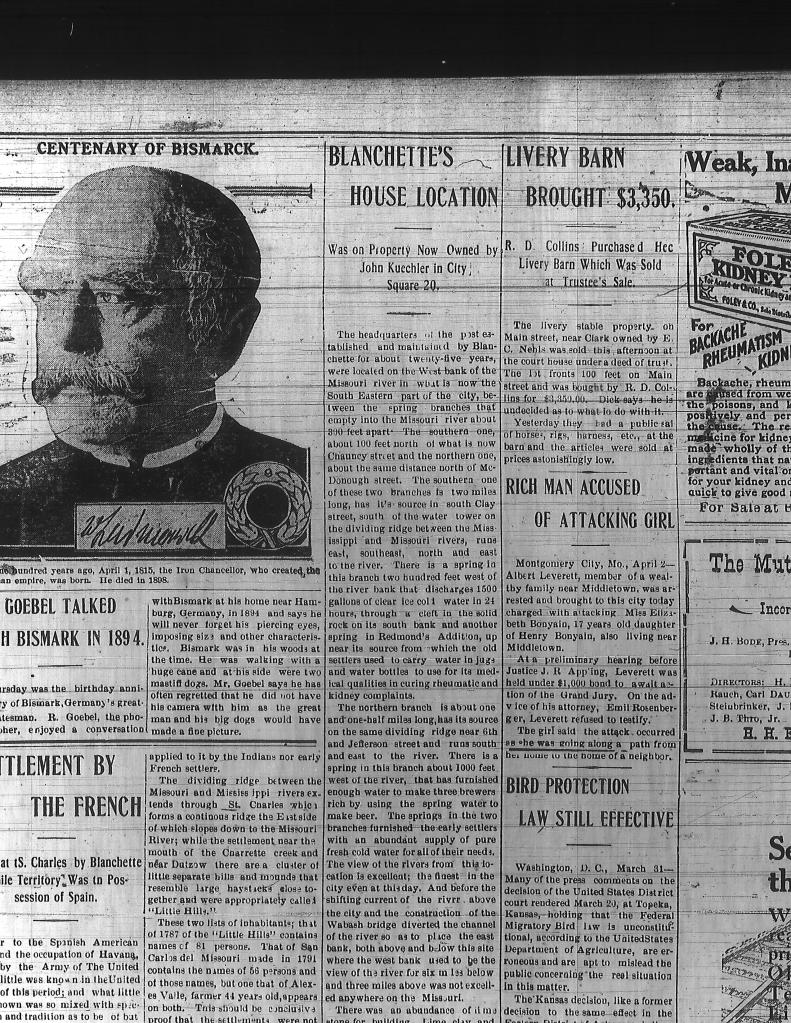

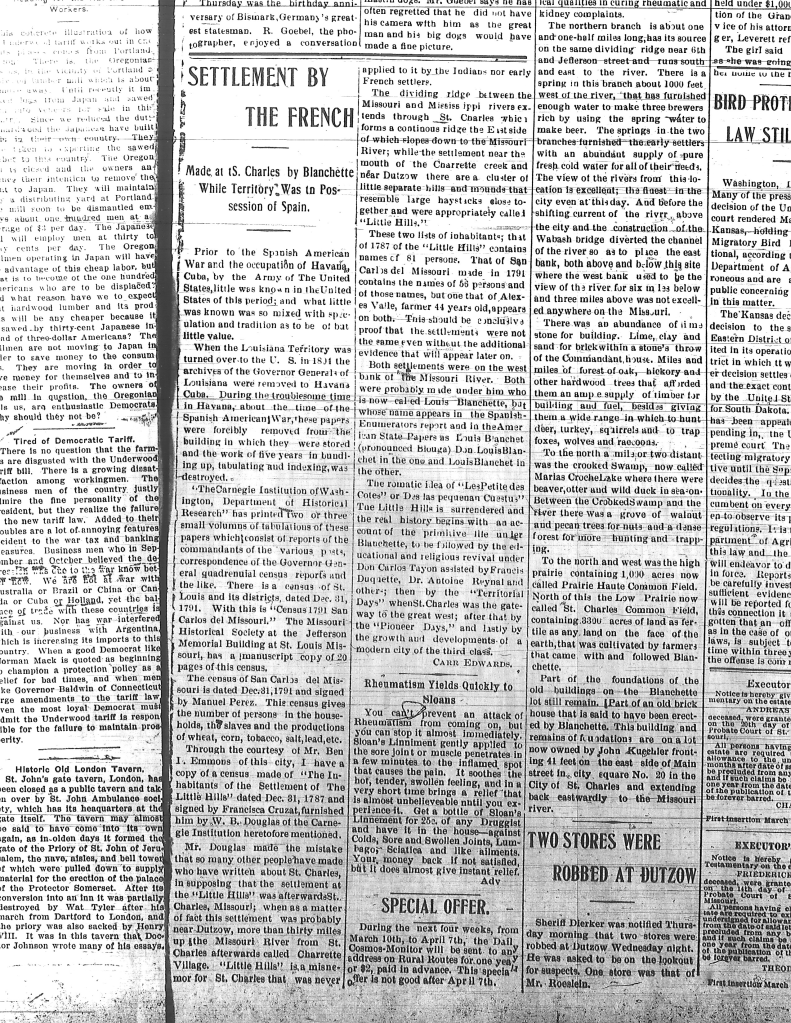

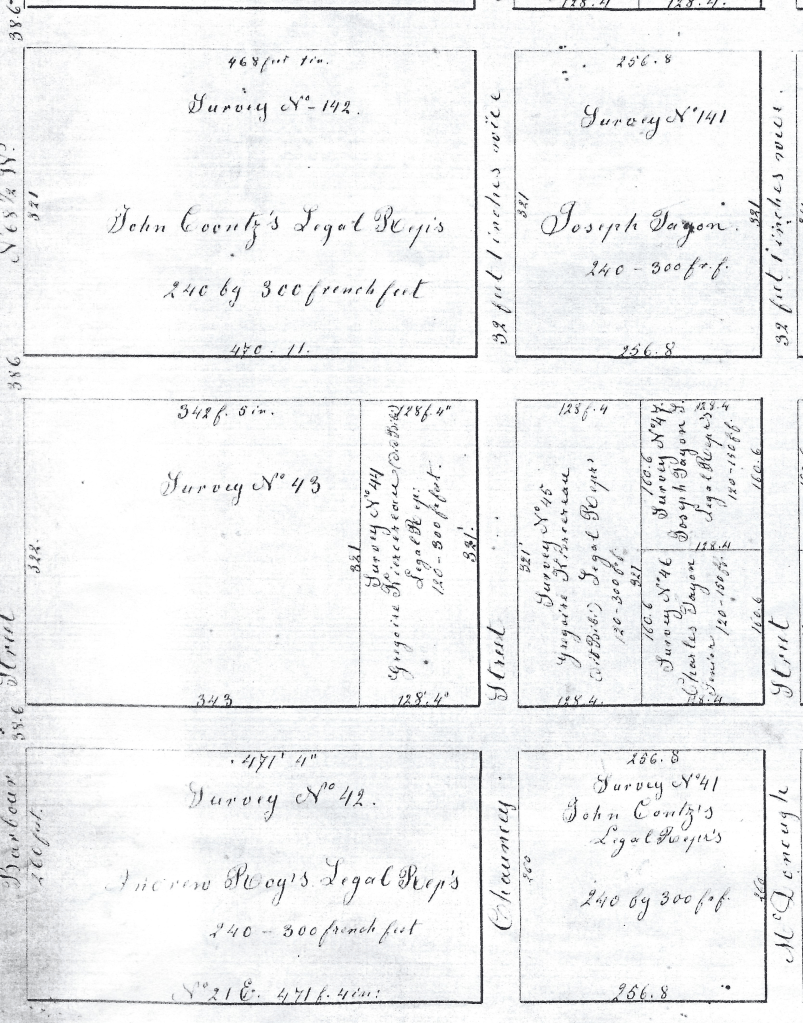

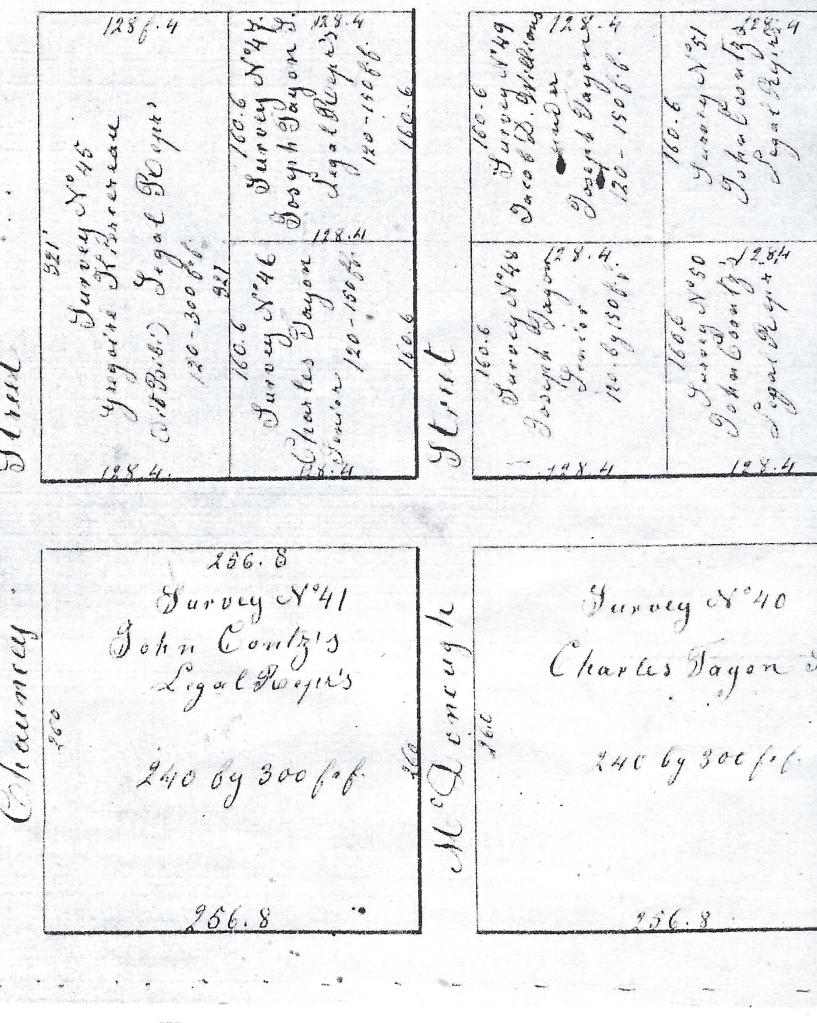

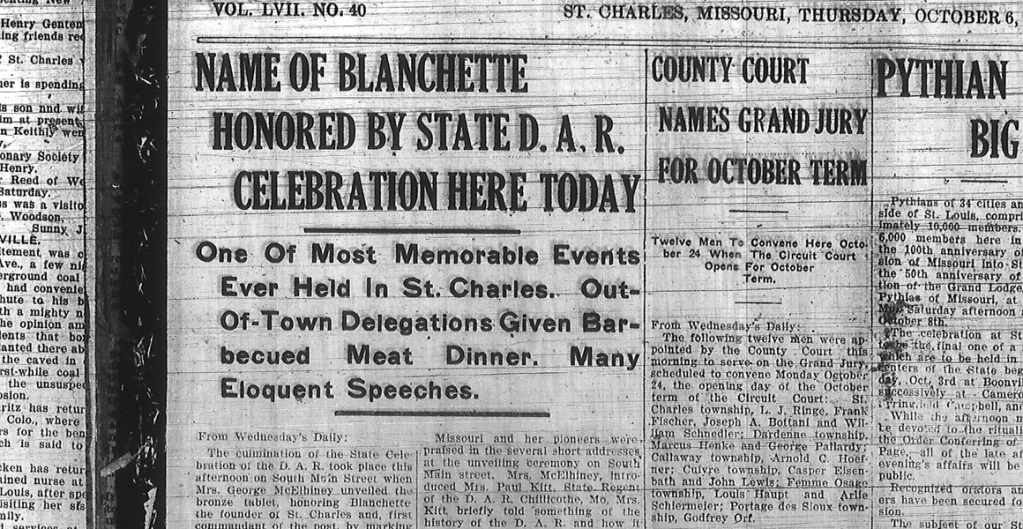

Block 19 was the only block claimed for Blanchette until the research of Carr Edwards uncovered a tract of land, originally claimed by Blanchette, given to the legal representatives of John Coontz. This research was first presented in one of the local papers on 3 April 1915 (see the 7 April 1915 weekly edition of the St. Charles Cosmos-Monitor below) and repeated in another article from Carr Edwards in the St. Charles (MO) Daily Cosmos-Monitor on 14 February 1916.[32]

Newspaper microfilm collection, Kathryn Linnemann Branch, St. Charles City-County Library District

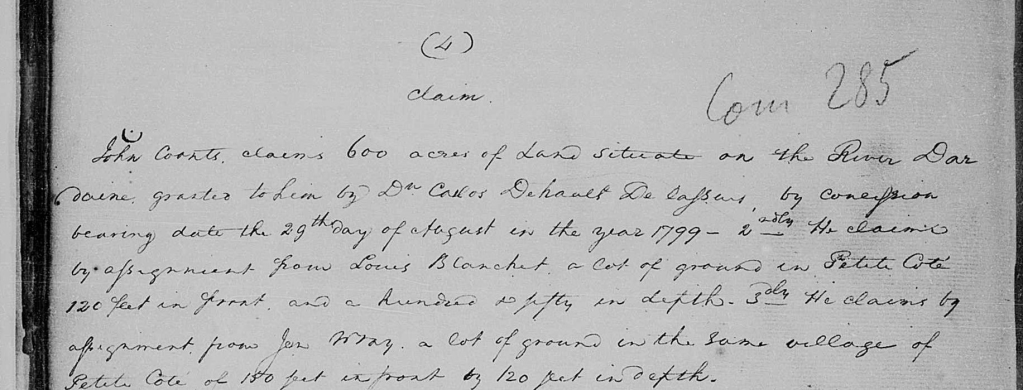

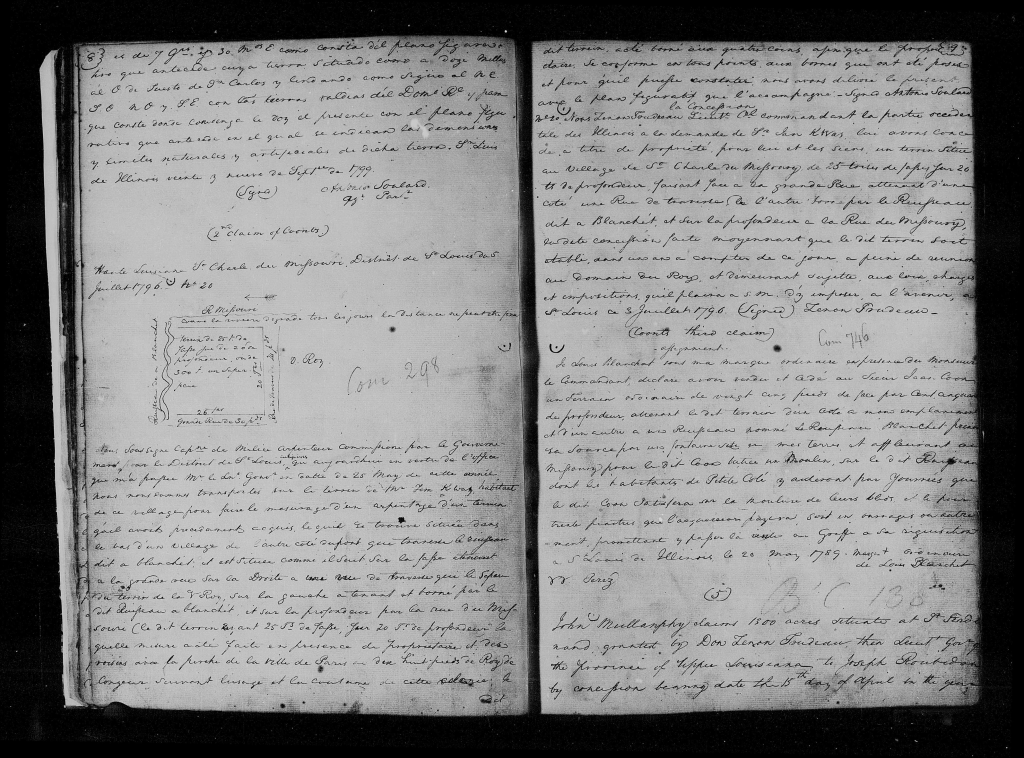

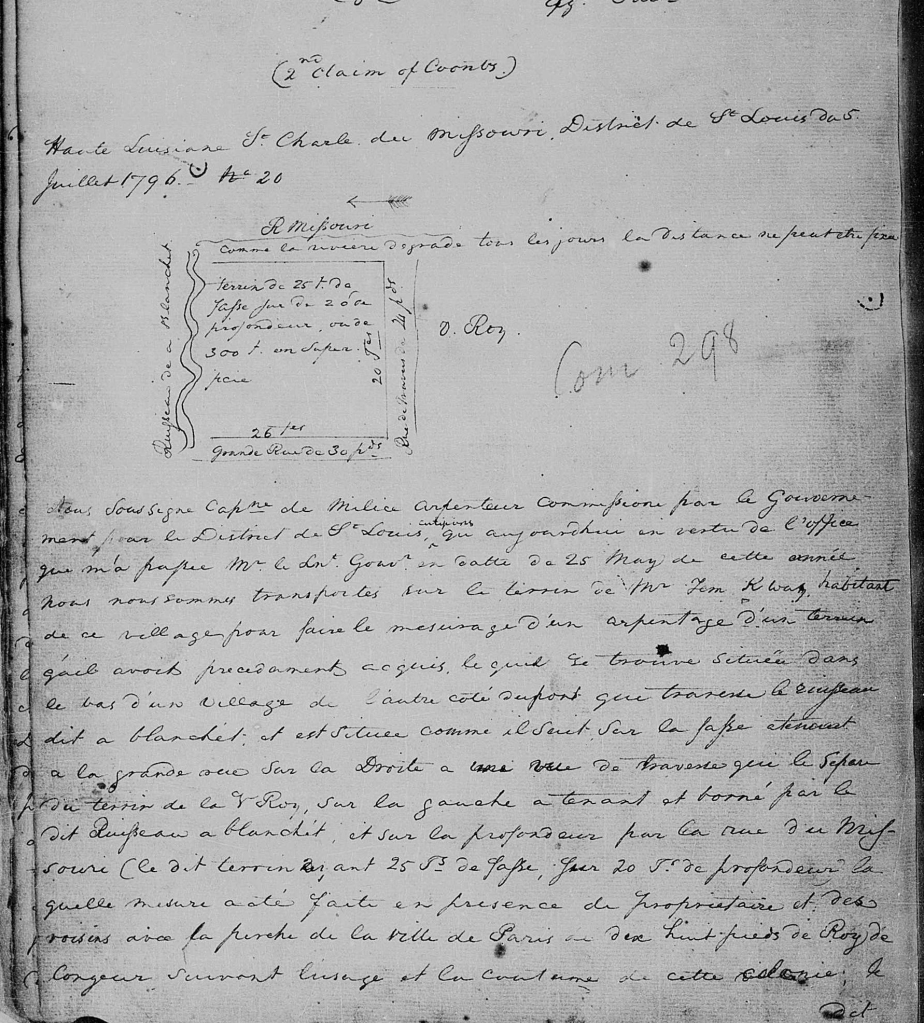

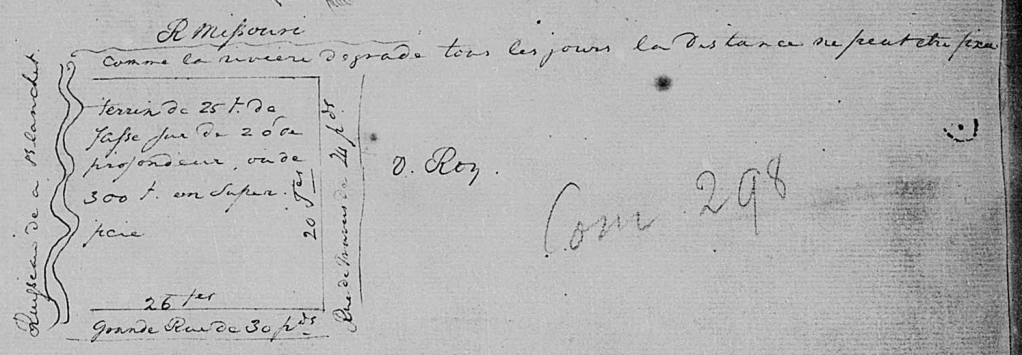

Edwards’ claim that Block 20 was the site of Blanchette’s house appears to be based on the American State Papers. A tract of land, originally claimed by Louis Blanchet, was awarded to the legal representatives of John Coontz on 1 June 1811. The nature of the claim was given as “ten years’ possession.” It was a lot in the Village of St. Charles; but the lot was 120 feet by 120 feet.[33]

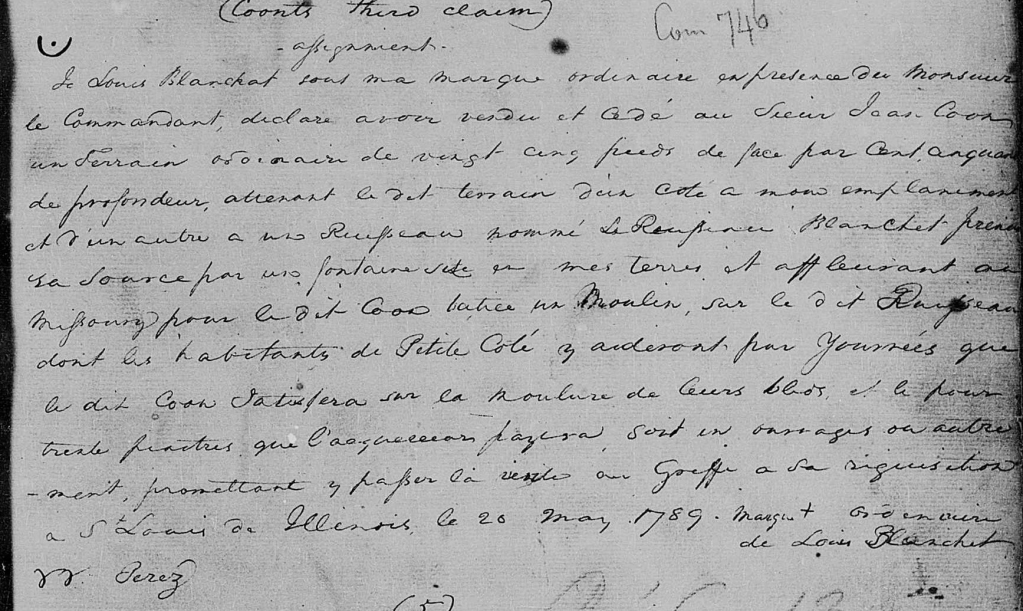

This may or may not be the same lot claimed by Coontz based on “a conveyance from said Louis Blanchette to claimant dated 20 May 1789, approved by Don Manuel Perez, Lieut. Governor.”[34] Edwards states that Coontz had no problem confirming this claim before the United States Court of Claims, but such a court did not exist until 1855.[35] Immediately, we encounter another problem as lots on the river side of Main Street usually extend back 300 feet to the river. Such is the case with Block 20, the entirety of which, 240 feet by 300 feet (French measure), was confirmed to the legal representatives of John Coontz.[36]

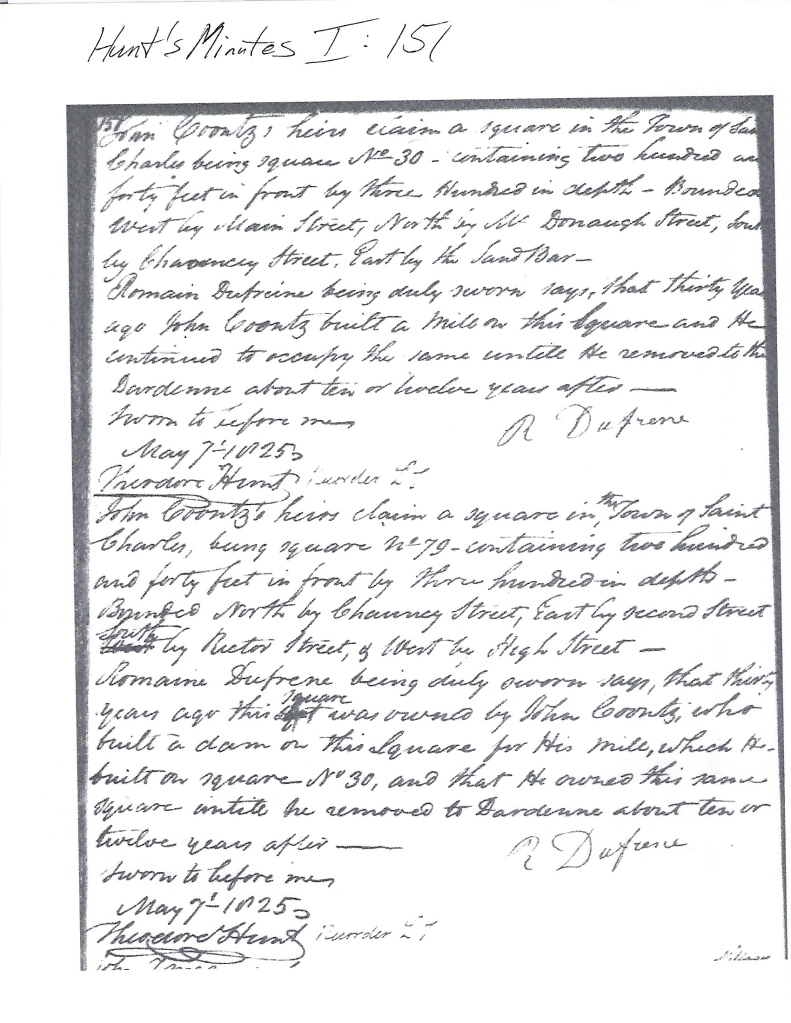

Further information on the provenance of the above property can be seen in the earlier round of land trials, officiated by three commissioners, one of whom was Hunt’s father-in-law, John B. C. Lucas. John Coontz laid claim to two lots in Les Petites Cotes in 1809.

Family History Library Film # 007842359

Family History Library microfilm collection

Film # 007842359

Even if the above parcel is located in Block 20 today, that does not negate Latrail’s testimony about the location of the first house built in St. Charles. Coontz also laid claim to two lots in Block 24.

from Theodore Hunt, U.S. Recorder of Land Titles (1825)

This map is at the St. Charles County Historical Society

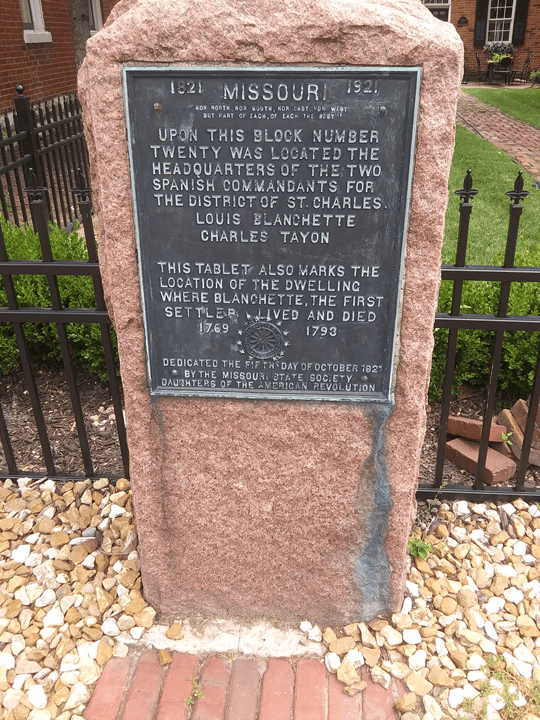

The chain of title for Block 25 (700 block of S. Main – west side) shows Blanchette’s son Pierre relinquishing any right or title Blanchette had in property there.[37] The Coons/Coontz/Countz/Kountz family owned several properties in St. Charles. Any one of them could be the property in question as it is difficult to establish all the property Blanchette would have owned. Edwards’ research was apparently taken as gospel truth and became the foundation for the placing of a monument in front of 906 S. Main in 1921.[38] The monument is still there. (It is possible that Carr Edwards’s research was based on data from the 1909 St. Charles centennial. For example, one local newspaper claimed in 1909 that “Louis Blanchette … built his cabin on its present site.”[39])

Photo #1111

Microfilm Collection, Kathryn Linnemann Branch, St. Charles City-County Library District

SCCHS Photo 13.1.042

Photograph by Justin Watkins, September 2019

Coontz’s residence here coincides with the age of artifacts discovered here by archaeologist Steve Dasovitch

This site may have been claimed for Blanchette as early as 1909

See earlier in the article for evidence refuting the claim that this was the site of Blanchette’s house

Photograph by Justin Watkins, September 2019

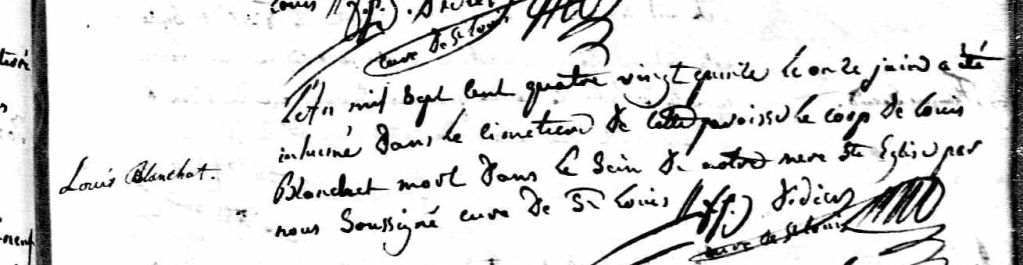

Louis Blanchette came from a Catholic area of Canada and it was not long before a Catholic church was built in Les Petites Côtes. “The first Catholic church was built by Blanchette in Block 28 in 1770,” claimed a 1921 newspaper article.[40] Father Sebastian Louis Meurin is said to have visited the new settlement in 1772. [41] Blanchette, meanwhile, does not seem to have had an official Catholic church in Les Petites Côtes. His son Pierre Blanchet was baptized on 29 October 1773 in St. Louis.[42] On 17 March 1774, Louis Blanchet filed a power of attorney, which he granted to Joseph Marie Papin for properties Blanchet had part ownership of in Canada. The document identifies Louis’ father as Pierre Blanchet and mentions Pierre’s second wife, Catherine Rousseau, and Louis’ sisters, Catherine and Genevieve Blanchet. At the time, Louis Blanchet is listed as a habitant voyageur living in St. Louis (Archive #2684, St. Louis Archives, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis).

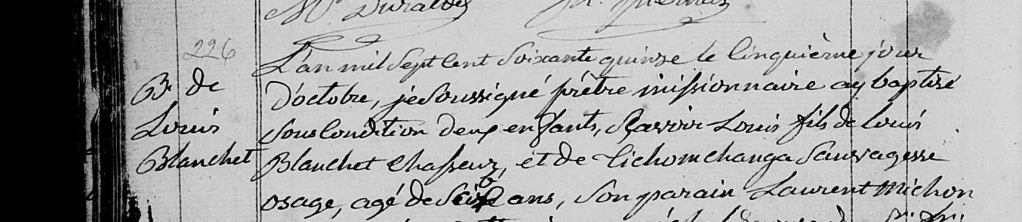

On 5 October 1775, Blanchette’s son, Louis Blanchet, Jr., was baptized in St. Louis by Father Meurin. Laurent Michon was the baptismal sponsor. It was noted at that time that the Blanchet family were residents of the Villages Des Petites Côtes.[43]

Family History Library Film # 007856505, Image 487

A 1941 Blanchet family history claims that the first church building was built of logs at the corner of Main and Jackson streets in 1776.[44] In that year, the Blanchette family appeared in the St. Louis Census (I have since learned that this was a reconstructed census put together in 1976 by the St. Louis Genealogical Society from a variety of records from circa 1776).[45] Emmons believes that the first church was not constructed until 1779 or 1780. [46]

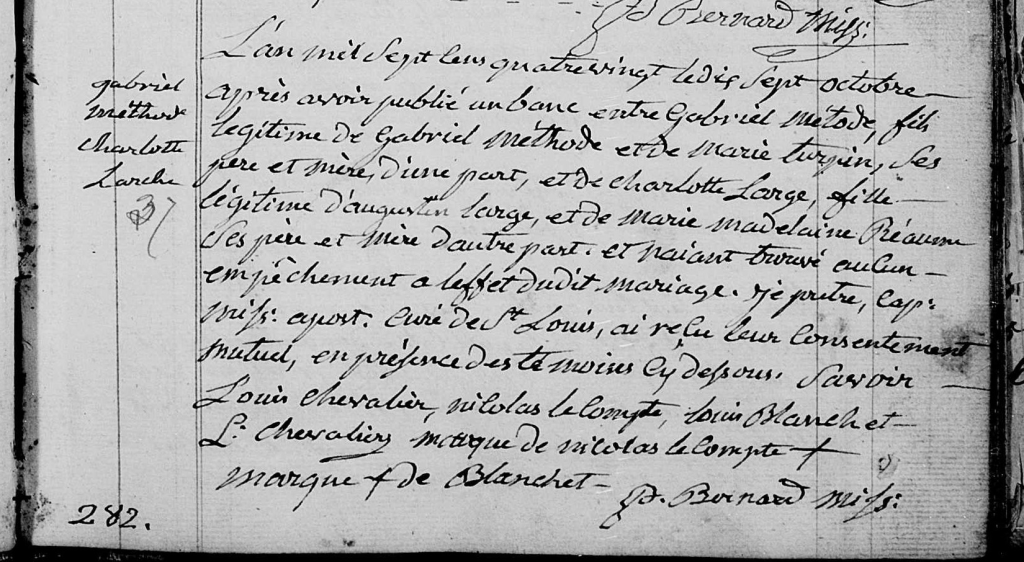

Growth of Les Petites Côtes (later Villages des Côtes) suffered from the lieutenant governor of Upper Louisiana’s discouragement of settlement outside of the district of St. Louis from 1780 to 1786.[47] In 1780, Louis Blanchet witnessed the marriage of Gabriel Methode and Catherine Marechal.

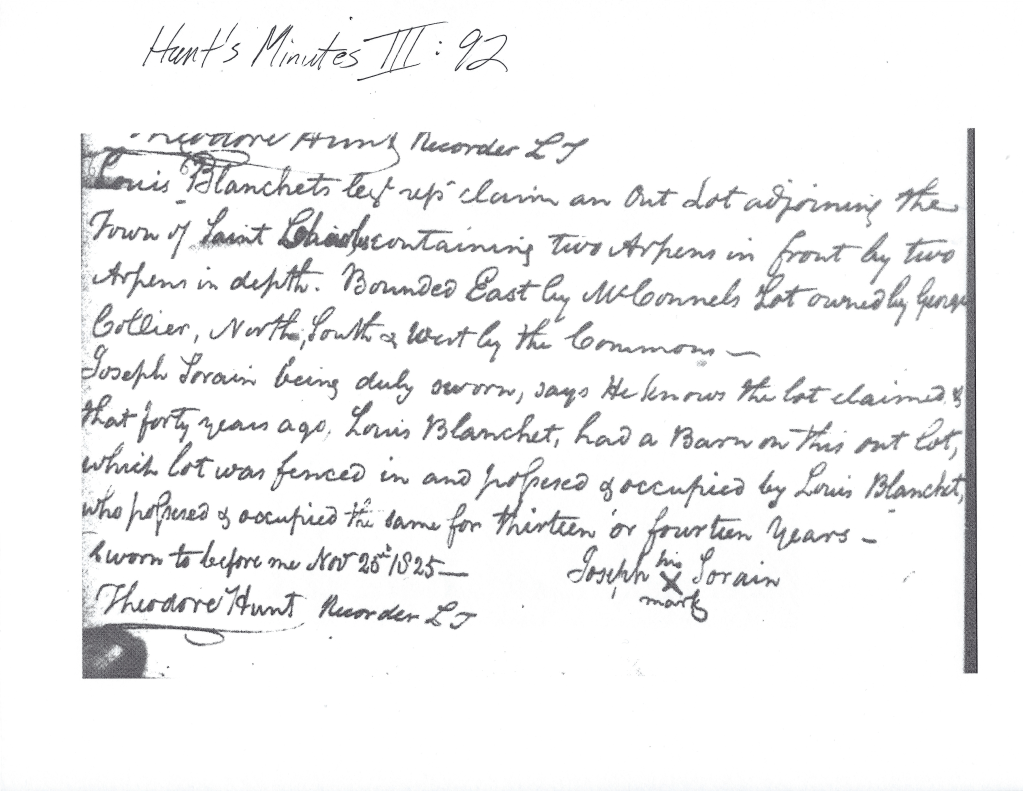

Family History Library Film # 007856505, Image 517

“Luis Blanchet” appears in the St. Louis Militia list of 5 July 1780. It is possible, therefore, that Blanchet participated in the Battle of Fort San Carlos on 26 May 1780 (Compañia de Melicias del Pueblo de San Luis, 5 July 1780, Archivo General de Indias, Cuba 2, fols. 566-568, cited in Molly Long Fernandez de Mesa, Mary Anthony Start, and Kristine L. Sjostrom, “Spanish Illinois Lists: What They Reveal About the Illinois Settlements During the American Revolution,” in Stephen L. Kling, Jr., The American Revolutionary War in the West [St. Louis: THGC Co., 2020], 182). In 1781, there were no more than six dwellings in Les Petites Côtes.[48] The earliest histories of St. Charles state that the village name changed from Villages des Côtes to San Carlos in honor of King Charles IV of Spain in 1784. [49] The settlement slowly attracted attention from others. Joseph Lorain arrived in 1784 and later gave testimony to Blanchet’s ownership of “an out lot adjoining the town of St. Charles, two arpens front by two arpens deep” in 1825 to Theodore Hunt, U.S. Recorder of Land Titles.[50]

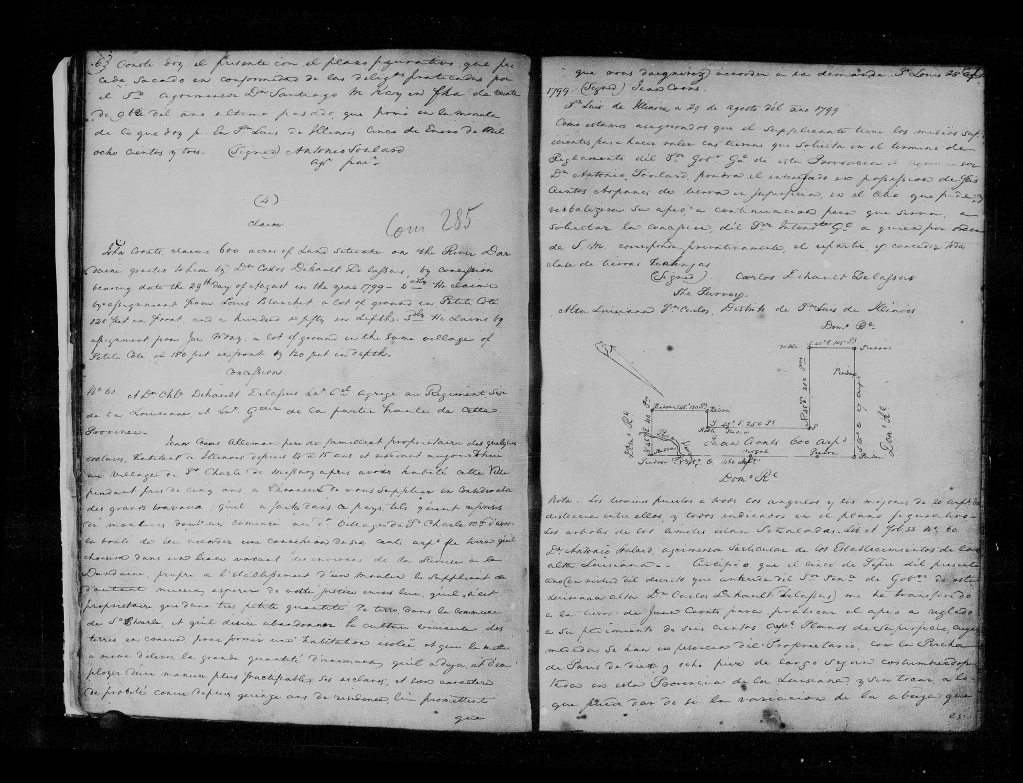

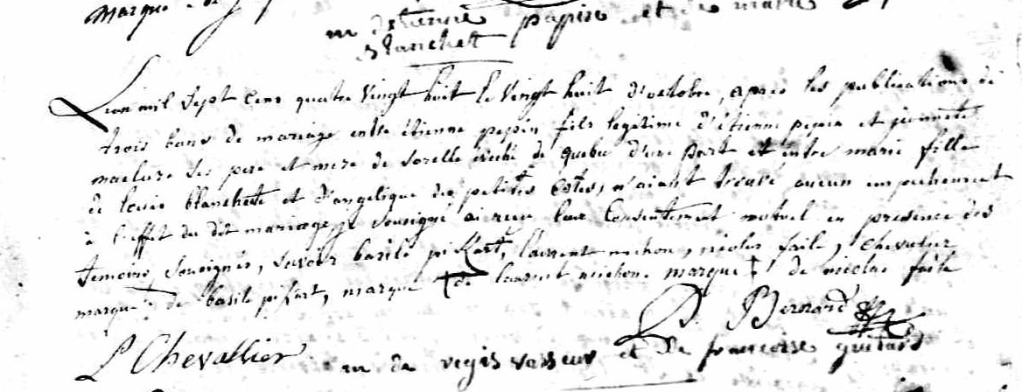

Microfilm Collection, Headquarters Branch, St. Louis County Library

The first village census was taken in 1787 and the fledgling settlement was called “Establecimiento de las Pequeñas Cuestas” or Village of the Little Hills.[51] There were eighty inhabitants at the time. The first survey of Villages des Côtes was done by Auguste Chouteau in 1787. He later testified in 1825 that St. Charles was founded by Blanchette in 1769.[52] Blanchette’s daughter, Marie “of Petites Cotes,” married Etienne Pepin 28 October 1788, a marriage recorded in the St. Louis Archdiocese records.[53]

Drouin Collection

U.S. French Catholic Church Records, 1695-1954, Ancestry

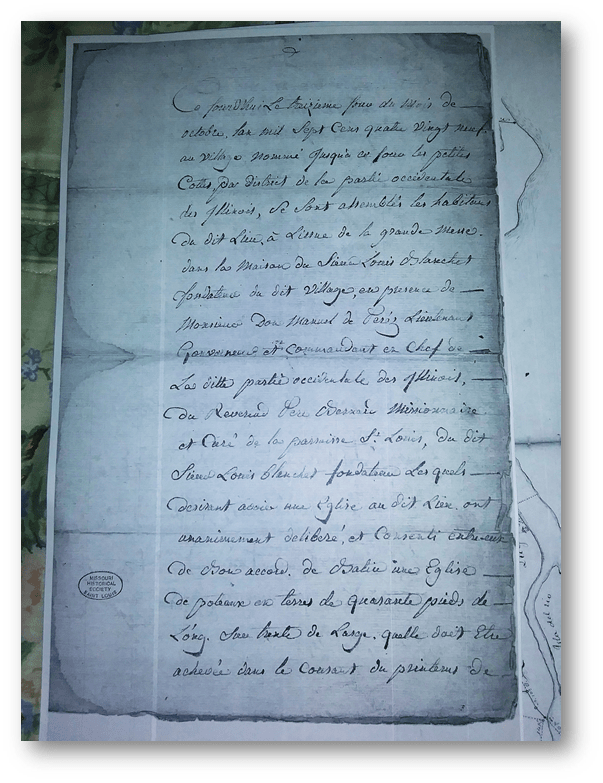

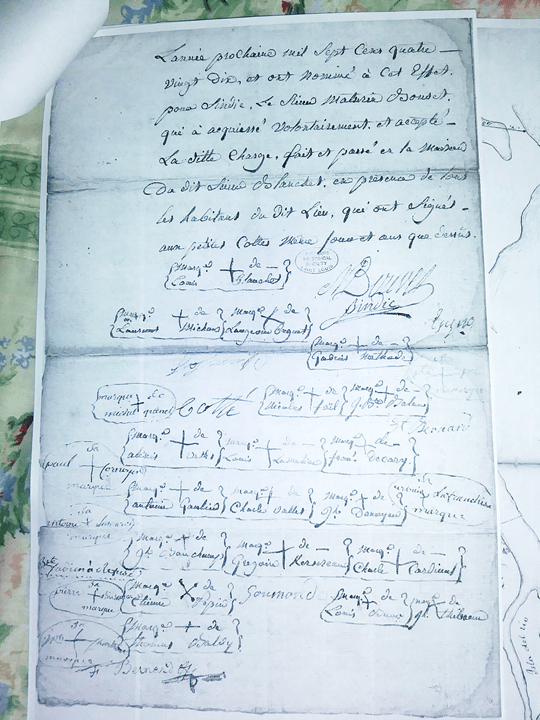

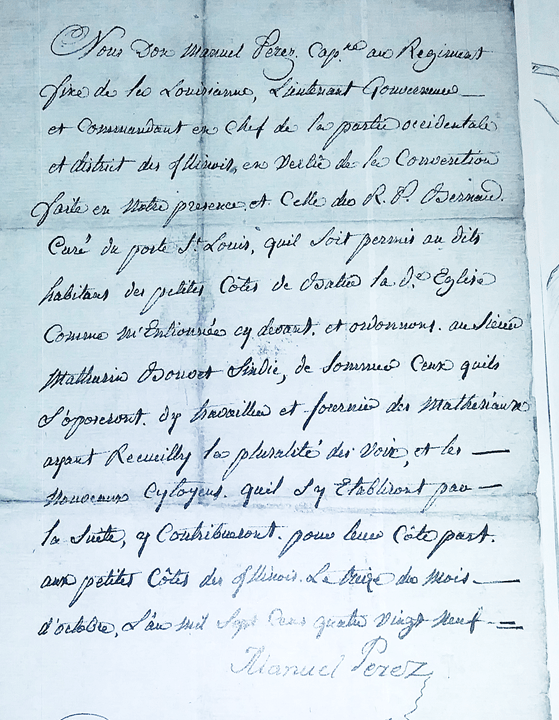

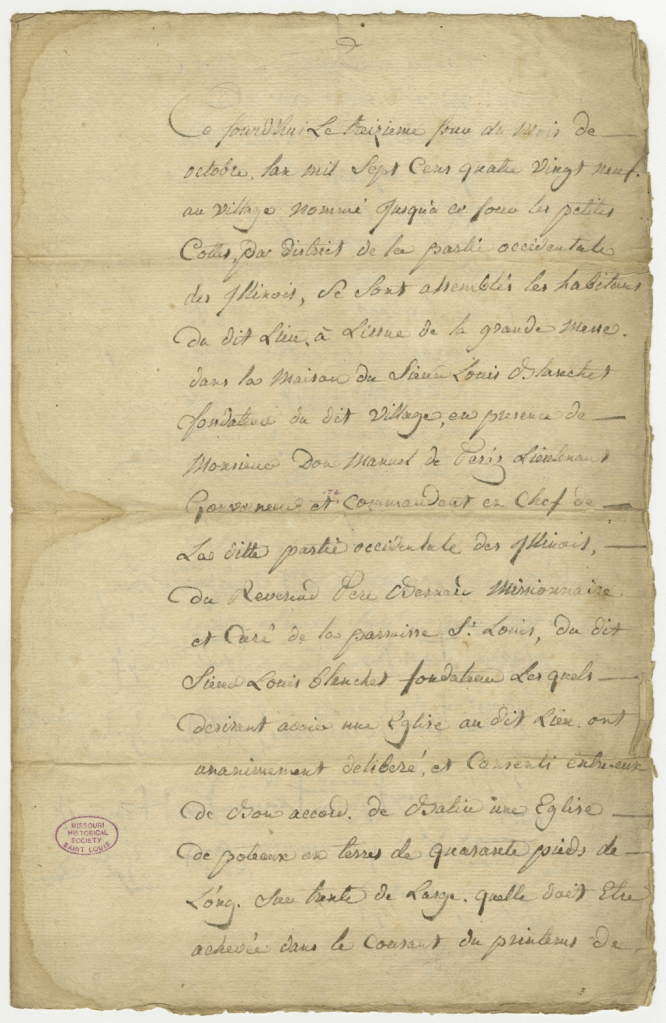

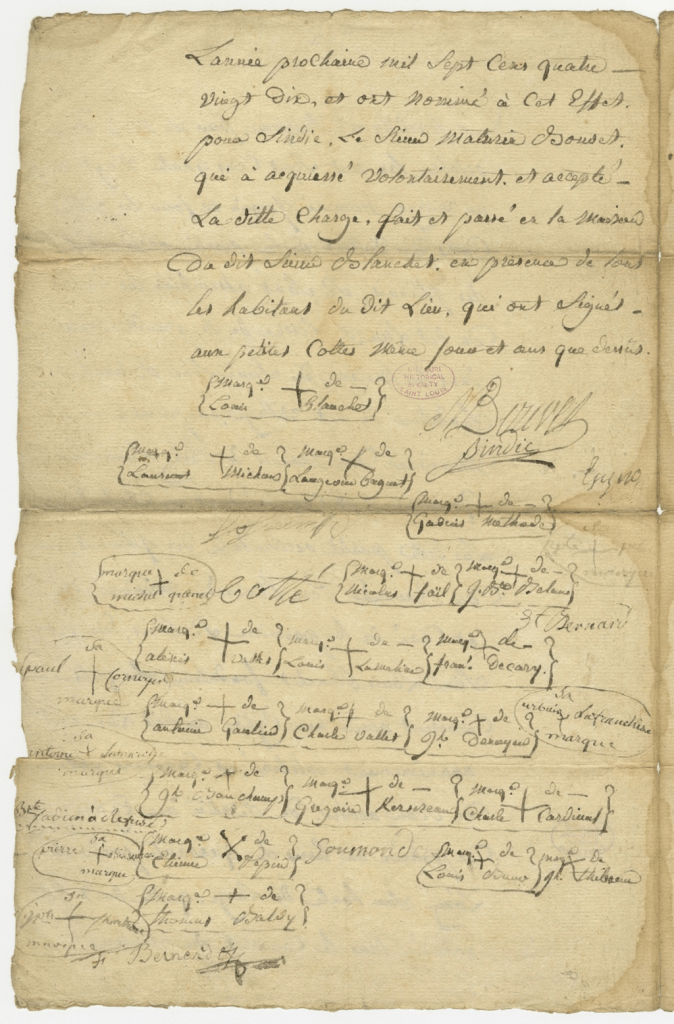

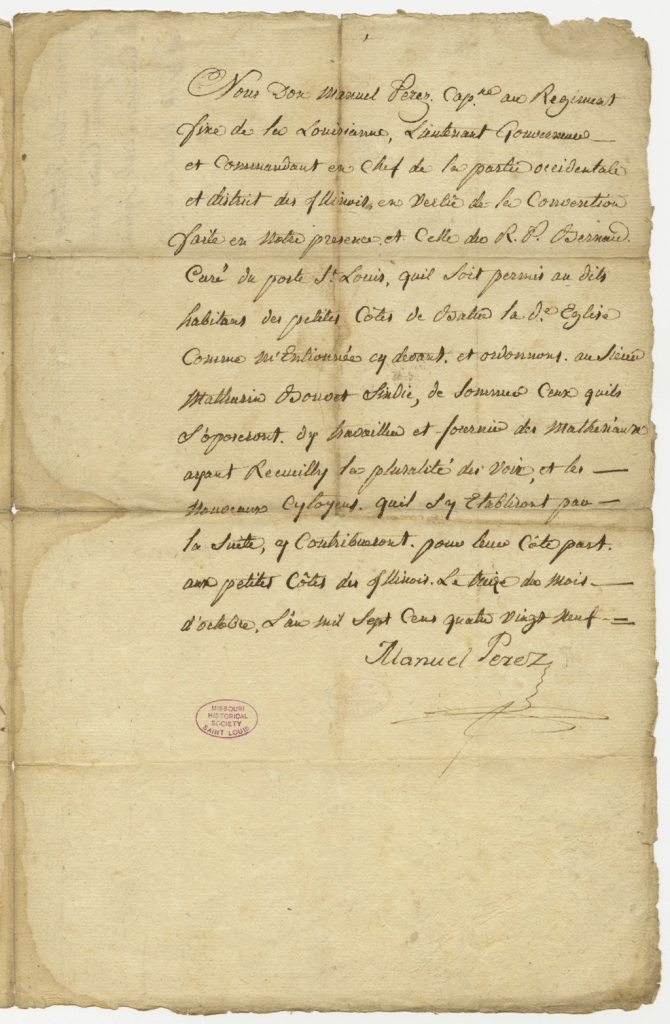

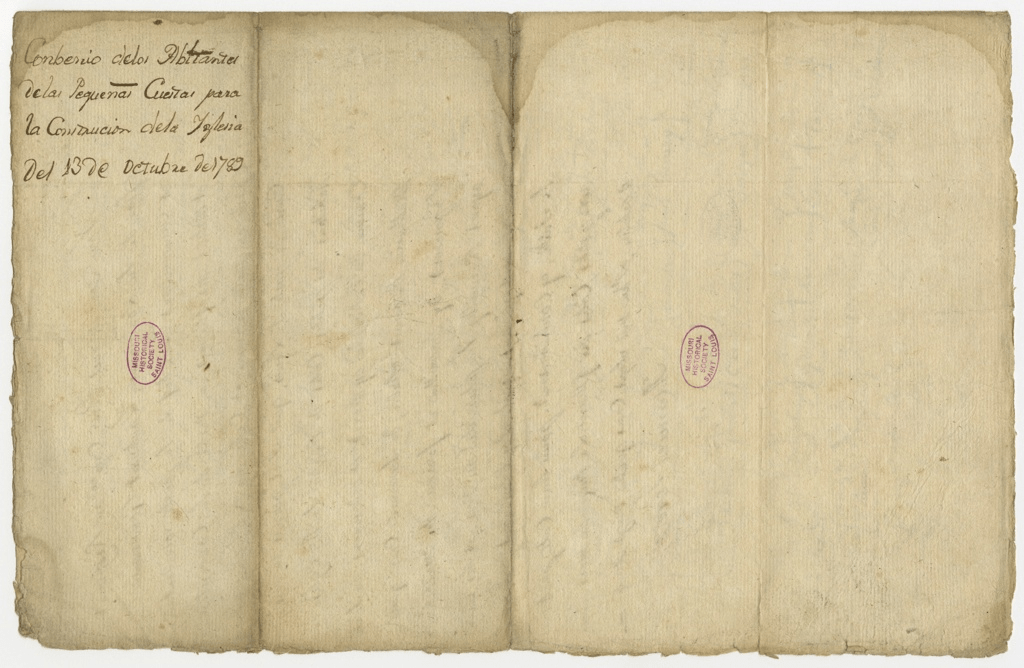

Blanchette closed out the 1780s by conveying a lot in the town of St. Charles to John Coontz on 20 May 1789.[54] On 13 October 1789, Lt. Gov. Manuel Perez authorized and agreed to have a log church constructed at Les Petites Côtes. The agreement was signed by thirty-one inhabitants.[55]

The village of Les Petites Côtes

To have a church created in the

Village, St. Charles Papers,

Missouri Historical Society

Library and Research Center

13 October 1789

The Missouri Historical Society has since digitized this document:

The above images are taken from https://mohistory.org/collections/item/A1339-00003

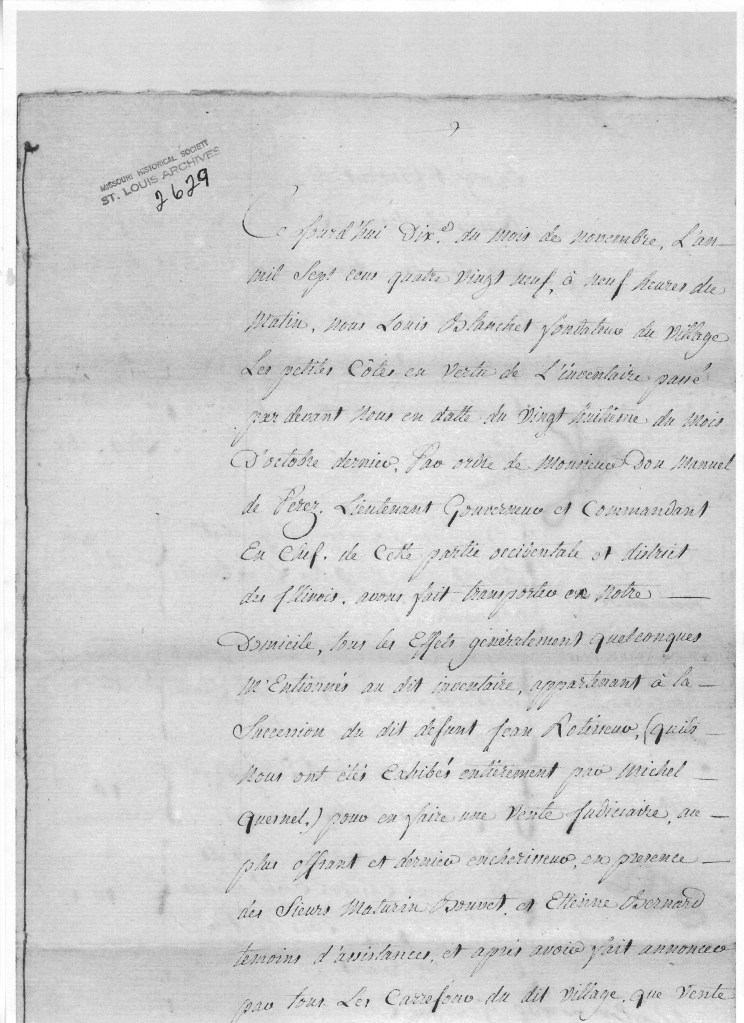

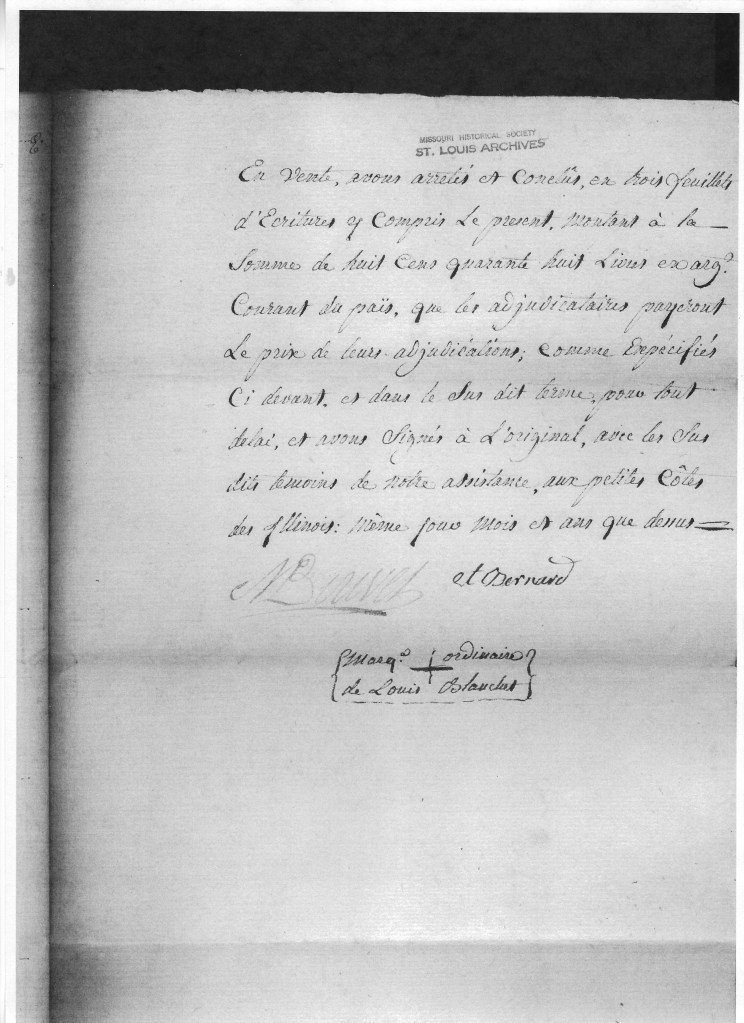

On 10 November 1789, he is listed as the founder of the village of Petites Cotes (St. Louis Archives, Archive No. 2629, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis).

Below is the first page of that document, photocopied at the Missouri Historical Society Library and Research Center in St. Louis.

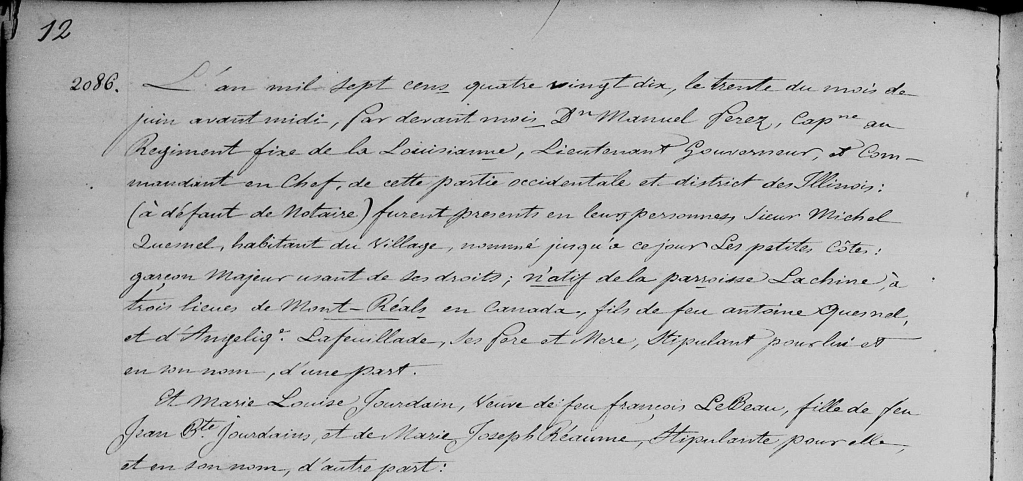

Family History Library Film # 007513787 (Below image is #12)

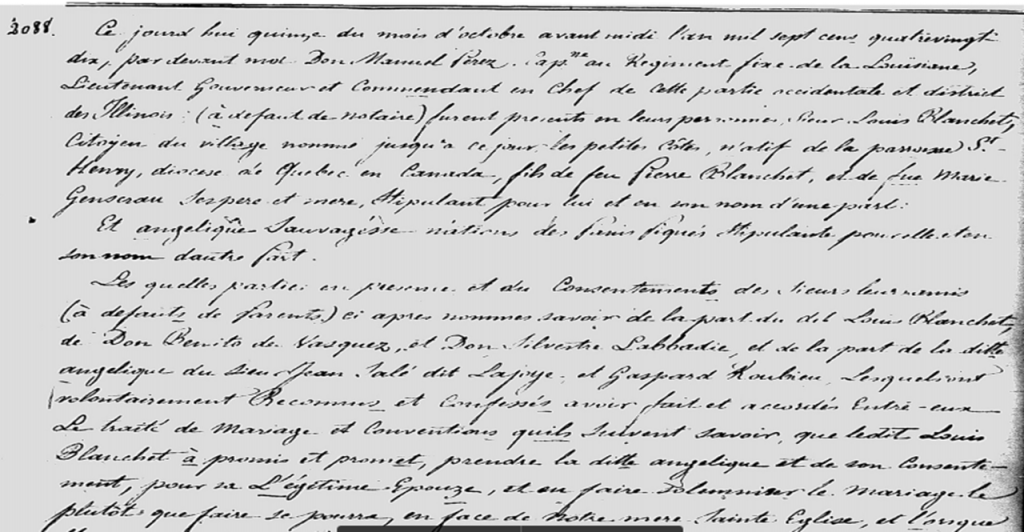

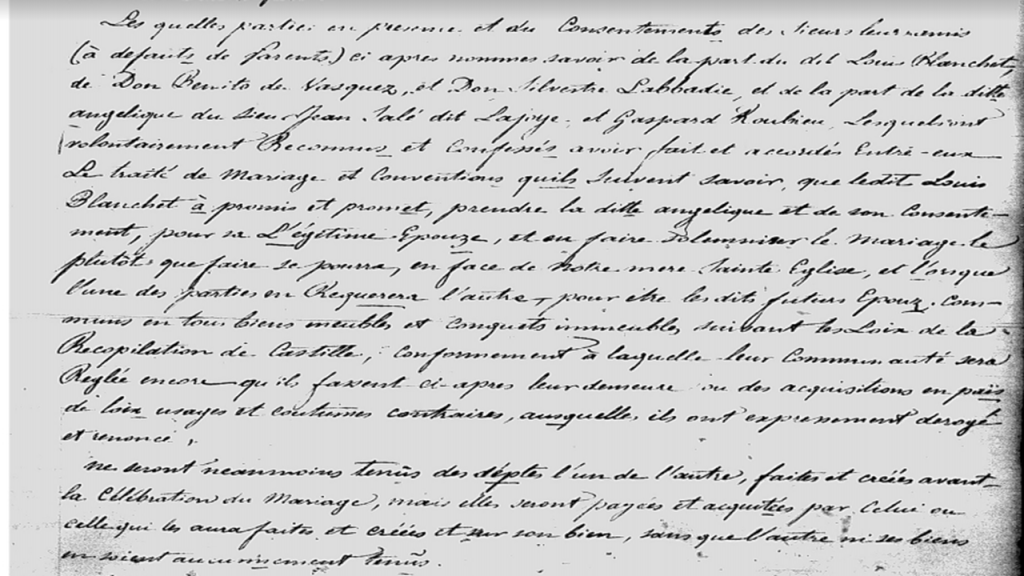

On 14 October 1790, Louis Blanchette officially married his common-law wife, Tuhomehenga. She was baptized the previous day along with their grandchild, Angelique Pepin.[56] Although Riddler claims that the information that Blanchet’s parents were Pierre Blanchet and Marie Gensereau was based on the research of Father Cyprian Tangray, but the below document disproves that claim. The information came directly from that given by Blanchet at the time of his marriage in 1790 (Riddler, 35).

Tuhomehenga took the name Angelique. Blanchette’s fledgling settlement receives another mention in the St. Louis archives:

Family History Library Film # 007513786

On 16 June 1790, Father Jean Antoine Ledru visited Les Petites Côtes, “where they intend constructing another church, which will be the second branch of this one. After all these ceremonies and, having dined with all the guests at the house of the founder, they returned to this post without accident.” [57] Another son, named Louis Blanchet, was born to Louis Blanchette and Angelique in 1790. Louis, Jr., died at the age of five on 5 April 1795.[58]

Drouin Collection

U.S. French Catholic Church Records, 1695-1954, Ancestry

Another census of San Carlos de las Pequeñas Cuestas was taken in 1791. Here, Blanchette appears at the head of the list of the heads of household. St. Charles Borromeo Catholic Church was officially dedicated on 7 November 1791. The following day, another order gave Blanchette power to punish those who did not attend church, which was required by the Spanish government.[59]

Settlements such as St. Charles sometimes dealt with Indian attacks. Manuel Perez reported in January 1791, “At the end of last month, the savages killed two men, bachelors, while they were hunting in the Missouri thirty leagues from the establishment of San Carlos de las Pequeñas Cuestas.”[60] Another incident occurred on the site of the Spring Mills Estates subdivision off Muegge Road. This area was part of the St. Charles Common Fields, an area where the settlers kept horses to help in their farm work.[61] “In the early dawn of a Wednesday morning on 14 September 1792, the inhabitants of San Carlos del Misury lay sleeping in their small log homes at the foot of the hills,” wrote Lindenwood Professor Jean Fields. “Two men had guarded the herd that night, not nearly enough to ensure the safety of the horses, but most of the habitants were away hunting on the Upper Missouri. The shortage of guards was a perpetual problem; the Indians considered horses fair game and frequently attempted to steal one or two if the opportunity arose.”[62] 1792 was not a good year for crops. “The spring of 1792 had been” unseasonably “cold. Winter lingered into May with sleet and periodic frosts. Planting had to be delayed. When the crops were finally in, torrential rains began and, soon, most of the crops were rotting in the ground. Some of the seed proved defective, especially the wheat and the corn.” Per Fields, San Carlos del Missouri contained 337 residents.[63] In September, Louis Blanchette dispatched pirogues to Ste. Genevieve to trade for corn. They paid for the grain with their hard-won furs, bear tallow, and hides. This meant they had few trade goods left to purchase the guns, axes, lead, powder, traps, and dozens of other items necessary to their livelihood … Slowly, the slender resources that sustained St. Charles were being drained away.”[64] The events of 14 September only added insult to injury. “Suddenly, the morning silence was shattered by war cries. A raiding party of mounted Iowa warriors burst through the trees, thrust the two guards aside, and swiftly began to round up the herd. The guards were badly outnumbered. Within minutes the Indians had stolen every horse in St. Charles and were driving them north towards the Des Moines River country.”[65] News of the theft was reported ten days later by Zenon Trudeau (1748-1813) to Francisco Luis Hector Carondelet y Bosoist, Baron de Carondelet (1748-1807), “On the 14th of the present month, the Iowa Indians, who inhabit the Des Moines River, which is 80 leagues distant from this establishment stole 38 horses from the establishment of San Carlos del Missouri. They were the only horses which the poor inhabitants had for working their lands. This district of Illinois is sadly lacking in animals. Because of the bad harvest of wheat this year, flour is valued at eight pesos for cwt. And if it were not for the harvest of maize in Ste. Genevieve being good, the inhabitants would not have had anything to live on all this year.”[66] Carondelet responded to the news, “This occurrence is all the more regrettable to me because it must be followed by the poverty which these inhabitants will experience because of the poor harvest of wheat and the small harvest of maize this year. You, who are in command of these places, must see if there is any remedy for what has happened, or if the Iowas are a nation from whom the stolen horses may be reclaimed, in which case you will do it and you will suggest to me the means which appear to you to be feasible.”[67]

According to Fields, “That winter Trudeau bent every effort to persuade the Iowas to return the horses. He dispatched messengers with threats, promises of gifts and more threats. His efforts dragged on into spring, but it was six months before he was able to report any progress, and even then, the tone of his letter is one of anger and despair.”[68] Trudeau reported to Carondelet in May 1793, “I have tried in every way possible to obtain from the ‘Nacion Ayoas,’ the thirty-eight horses stolen from the San Carlos establishment and through my orders and words sent to the leaders, they have killed the man that had committed said theft, promising they would return the horses this spring, a promise which as yet has not been fulfilled and a fact which makes me feel like sending another order demanding an answer on the first day. If I succeed in getting said horses, it will be the first satisfaction of this nature which this rule has achieved from the Indians, who in general are thieves now more than ever. Six Pus, whom I had cordially welcomed, upon leaving my house with a gift, have just stolen two mares and a horse two steps from town. This is the way these pests have always been, and they will remain this way with no remedy than a large population to punish these abuses from time to time.”[69]

The situation might not have changed if had not been for a group of Iowa Indians who went to buy horses from a group of Kansas Indians. The Iowa Indians there proceeded to kill eighteen and took twenty-eight women and children captive. In return for brokering a peace deal between the Iowa and Kansas tribes, Trudeau received thirty-seven horses from the Iowa. Just two months after his previous communication on this matter, Trudeau sent an update to Carondelet, “I have received the most complete satisfaction from the chiefs of the Indian nation for the theft of the horses which the men of the same had committed at the Post of San Carlos and even though they did not return the same horses, they completed the number with the exception of one which they paid for …”[70] In order to keep another incident like this from happening, a stone fort was erected on the site where the horses were kept. In later years, a barn was built around the structure. The stone walls of the fort were discovered in 2004 by employees of Fischer and Frichtel that were clearing the farmland for a new subdivision off Muegge Road. The building was dismantled by Lindenwood University and was hauled down to Boonesfield Village (now Lindenwood Park). In the summer of 2005, stonemasons rebuilt the walls based on drawings, pictures, and paint colors. “Lindenwood paid about $30,000 to move and rebuild the fort. The building is about 24 by 32 feet, and its walls are about 18 inches thick. It has a main entrance, and each wall has two gun-ports – openings wider on the inside and narrower on the outside. Although each stone isn’t back in the exact spot it was originally, the stones fit together surprisingly well, and the building looks solid and … fortress-like.”[71]

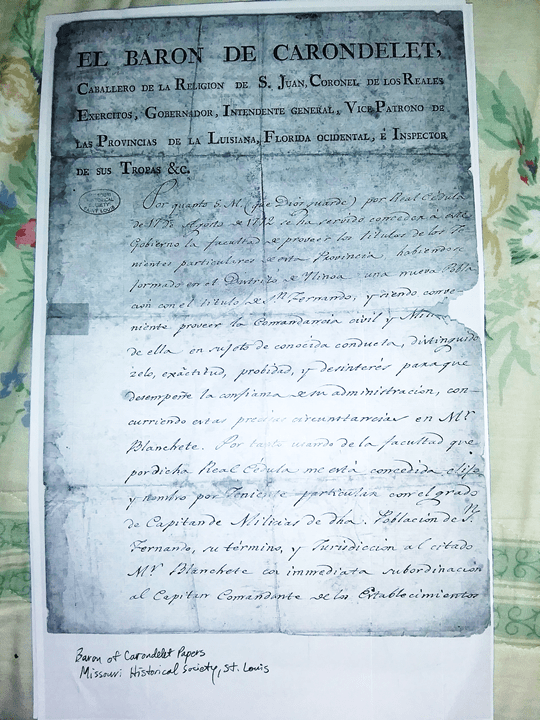

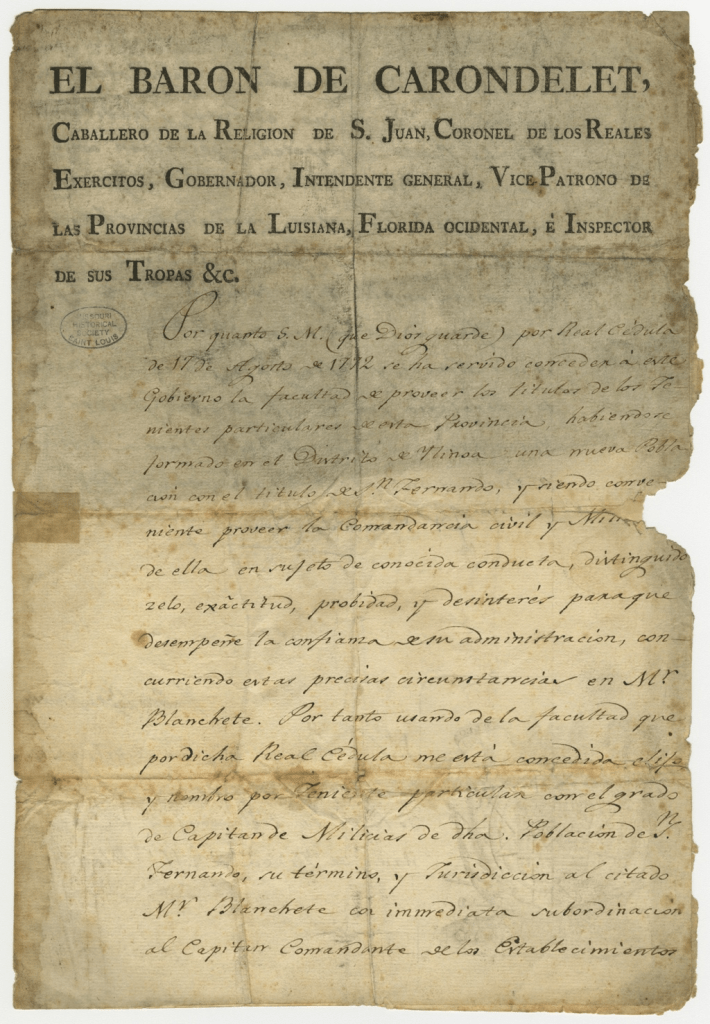

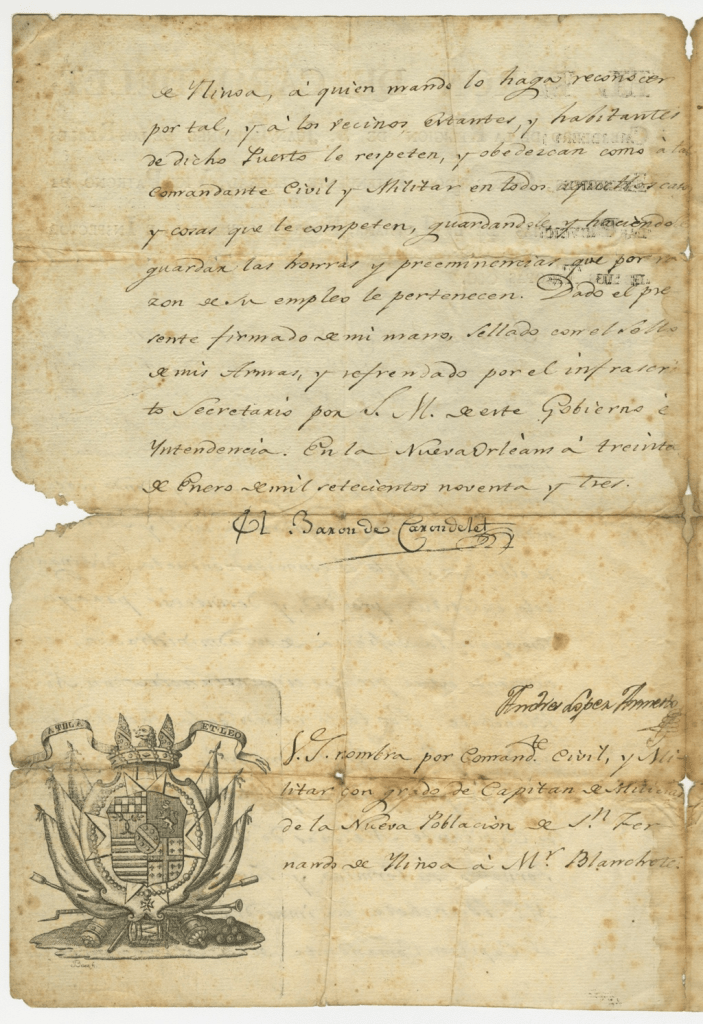

Louis Blanchette continued to serve as commandant until his death in late August 1793. “He died of a fever and was buried in September beneath the walls of a little Roman Catholic Church, which he had erected, and which was the first church built west of the Missouri River.”[72] He was laid to rest next to his wife Angelique, who had preceded him in death on 11 February 1793.[73] Regrettably, his name appears on few land records. On 25 September 1792, Blanchet officiated at the marriage of Jean Baptiste Prevot and Angelique of the Sioux Nation (Brown, 200 Years of Faith, 1 and Borromeo church records I: 1; Riddler 106-107; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, 21 April 1883, p. 16, Newspapers). On 9 October 1792, Blanchette, “Civil Commandant of Petites Cotes,” leased sixty arpens in the Prairie Haute Fields and forty arpens in the Prairie Basse via Mathurin Bouvet, notary, to Francois and Jean Malboeuf. [74] Blanchette approved the sale of livestock made by Charles Rielle dit Clements on 14 June 1793. Blanchette with seventy other citizens of St. Charles and citizens of St. Louis, St. Ferdinand, and St. Phillips, sent a letter to the king of Spain complaining of the governor of Louisiana, dated 7 July 1793.[75] The Baron de Carondelet issued an order making Blanchette civil and military commandant of “San Fernando” on 30 January 1793. [76]

Louis Blanchet as

Commandant of

San Fernando

Baron de Carondelet Papers

Missouri Historical Society

Library and Research Center

St. Louis, MO

31 January 1793

The above document has been digitized by the Missouri Historical Society of St. Louis.

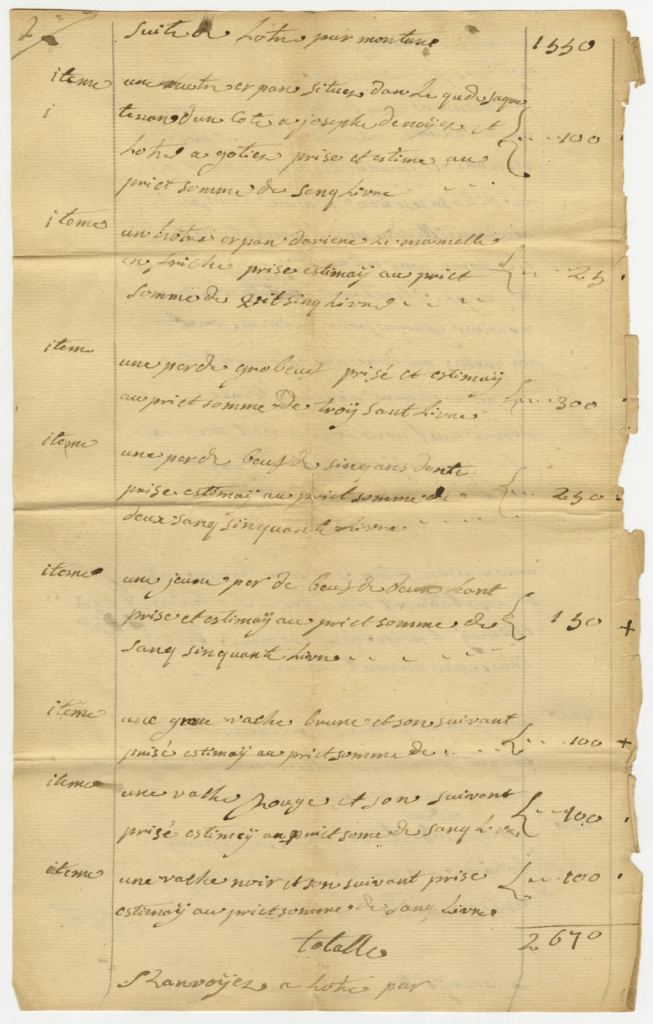

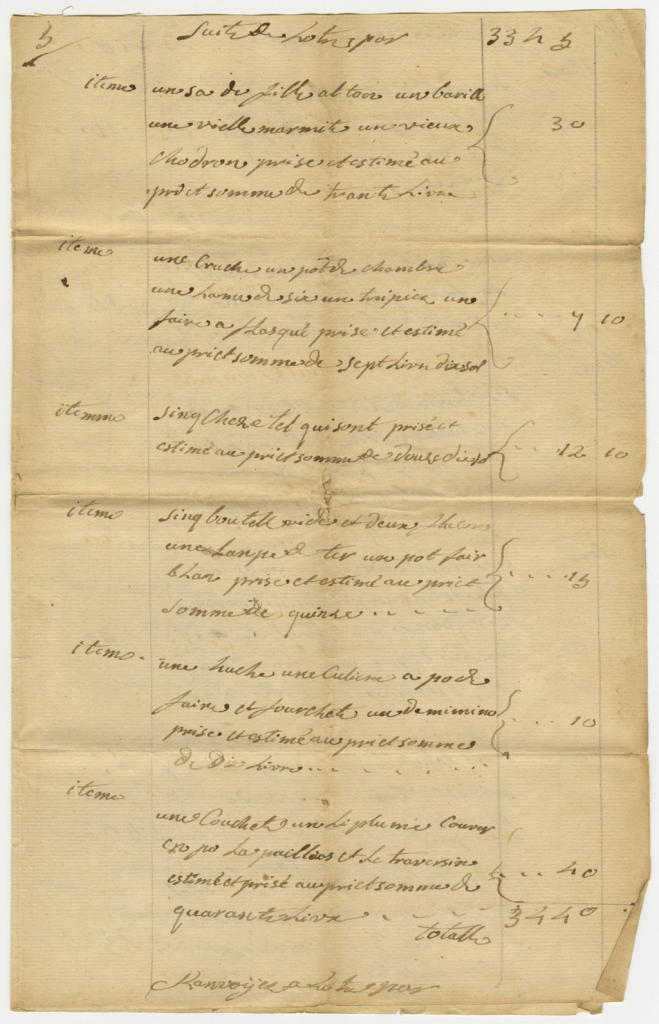

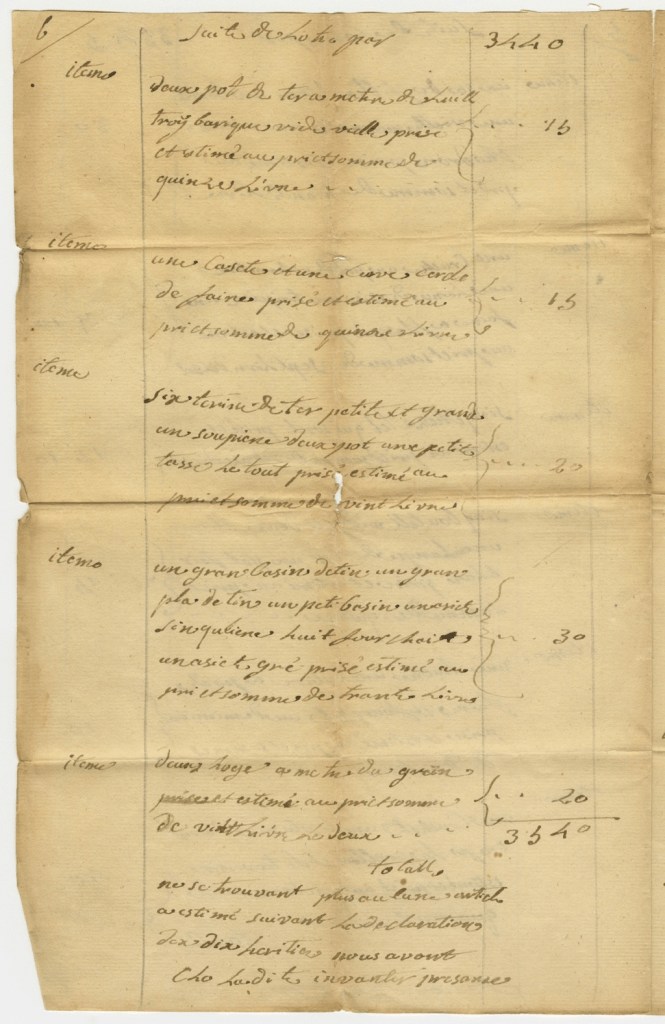

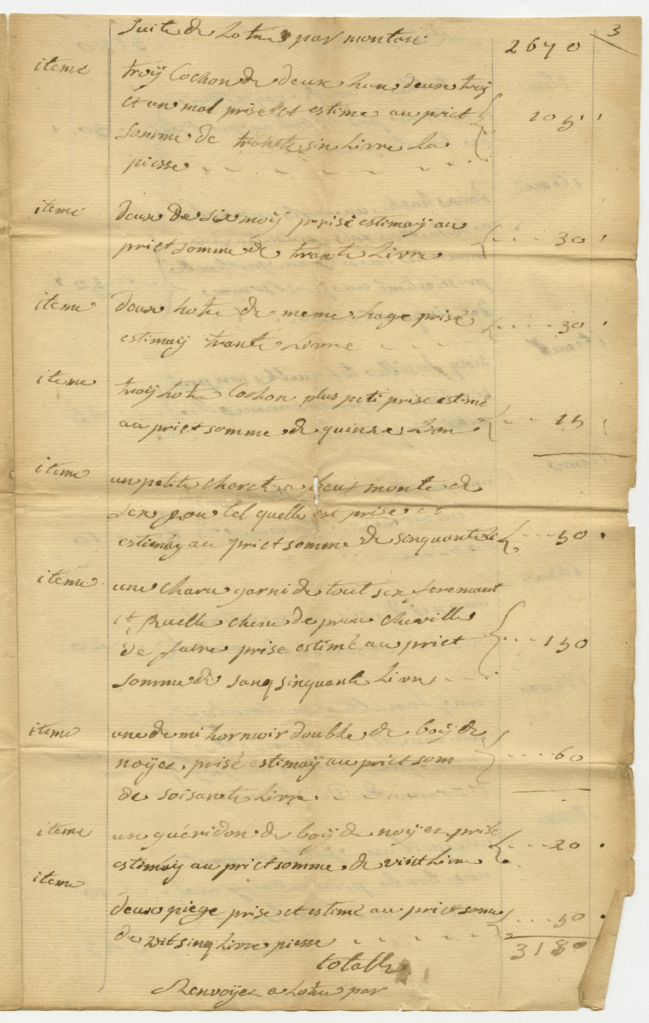

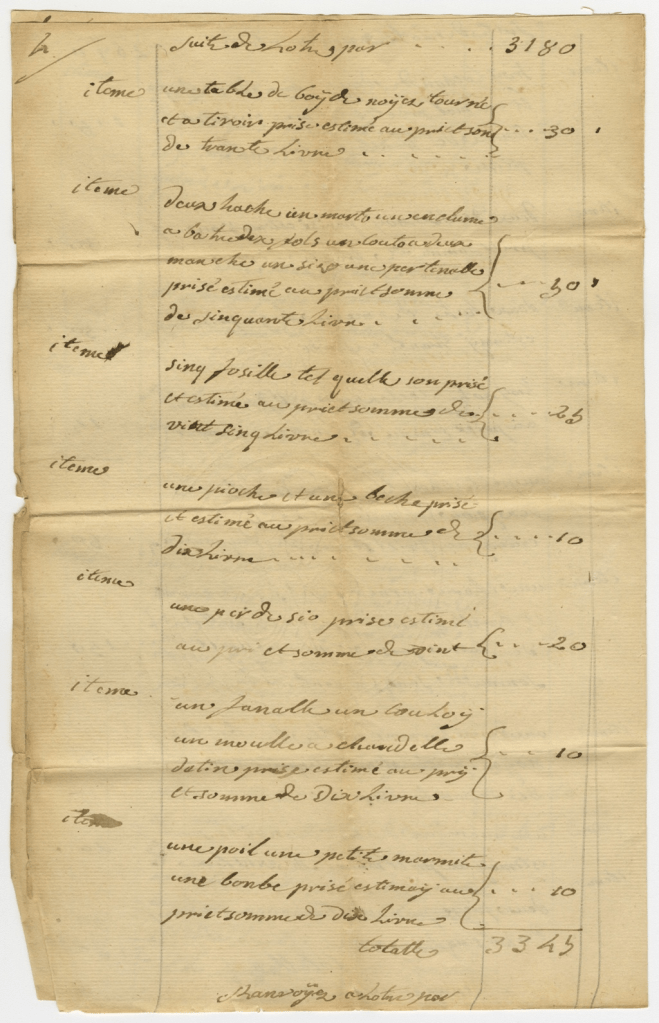

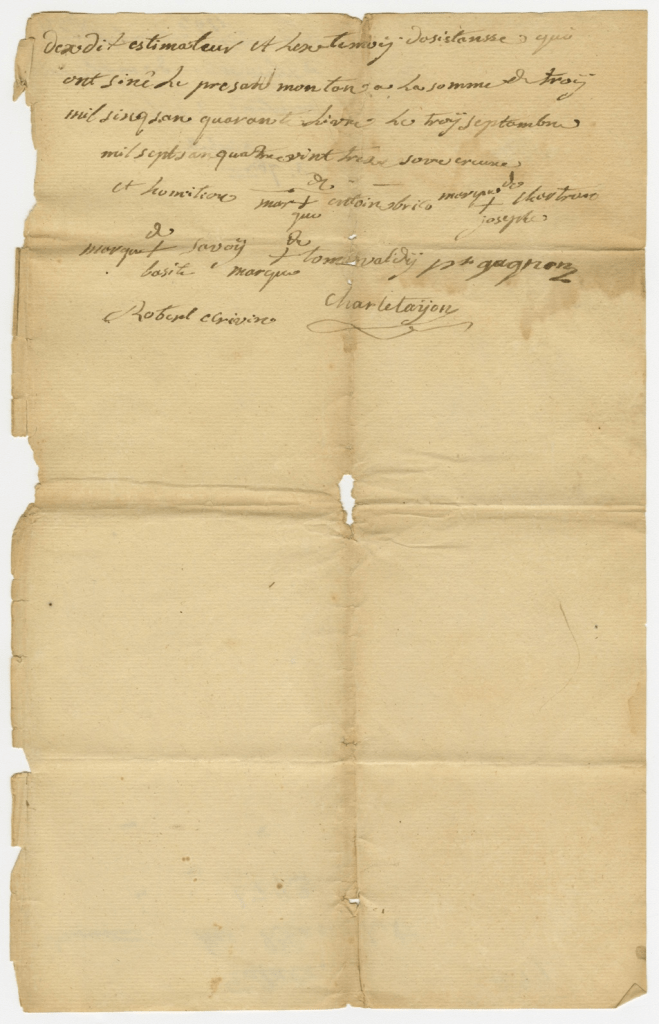

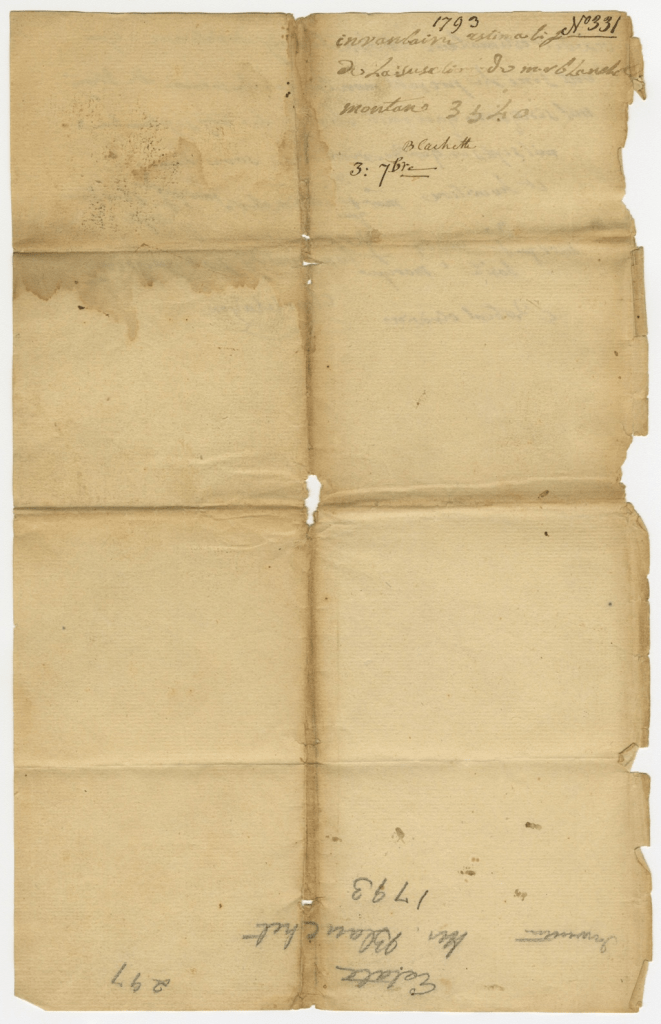

Blanchette’s estate was inventoried per request of his successor, Charles Tayon, on 3 September 1793.[77] The remains of Blanchette (and presumably his wife) are supposed to have moved with St. Charles Borromeo Cemetery twice, first in 1831 to the present site of the church at Fifth and Decatur streets, and again in 1853 to the present site of the cemetery on Randolph Street. The page that would have listed Blanchette’s burial in the St. Charles Borromeo records has been missing for a long time. Blanchette’s estate papers are at the Missouri Historical Society, which has more recently digitized them. The images are below.

Blanchette did not fully divest himself of all his property by the time of his death. The remaining property appears to have passed to his son, Pierre Blanchette of St. Louis County. Pierre Blanchette sold some of this land to Uriah J. Devore and David McNair in 1817 for $200. The properties included in the deed were a town lot in St. Charles and four hundred arpens near Marais Temps Clair north of St. Charles: “all my right, title, claim, interest, and poberty [hard to read] in and to the lands and town lots lying and being situate in the County and Town of Saint Charles, Missouri Territory, which was originally claimed or settled by my deceased father, Louis Blaunchette, and particularly all my right and title in and to a certain town lot situate in the Town of Saint Charles and bounded as follows, to wit: Northwardly by a cross street or alley, eastwardly by Main Street, which separates it from a lot belonging to the heirs of Pierre Troge, deceased, westwardly by the common lands of said town, and southwardly by a cross street which separates it from a lot belonging to the heirs of John Coons, deceased. Also, a tract of land lying and being situate in the county aforesaid near or at the Marais Temps Clair which was originally granted and settled by my deceased father as aforesaid, supposed to contain four hundred arpens.”[78] The following year, Pierre Blanchet deeded property he had inherited from his father to Devore and McNair for $10.[79] The land was located near the village of La Charette. Pierre Blanchette appears a third time in the St. Charles County deed records in 1818. This time he gave property to his brother-in-law Etienne Pepin on 28 August 1818.[80] Reference was made to an area known as the Barriere of Blanchette as being the boundary of St. Charles’ common fields in the Missouri Gazette on 16 October 1818.[81] Ten years later, the Blanchette name came up once again in a deed. On 28 December 1828, John Felteau of St. Louis sold to Thomas P. Copes of St. Charles a tract one arpen by forty arpens “in the Prairie Haute fields of St. Charles.” On the west side of the property was a lot of forty arpens “granted to Louis Blanchett.” [82] The Blanchette tract is Survey No. 185. It is the same property leased to François and Jean Malboeuf in 1792 and one-third of the Blanchette property in Prairie Haute Common Fields was owned by Lindenwood College in 1941 and included the site of Sibley and Irwin halls. [83] George C. Sibley purchased both the Felteau tract and an adjoining tract of forty arpens to the south, which had been confirmed to Louis Blanchette’s legal representatives, from Thomas P. Copes on 20 April 1829.[84]

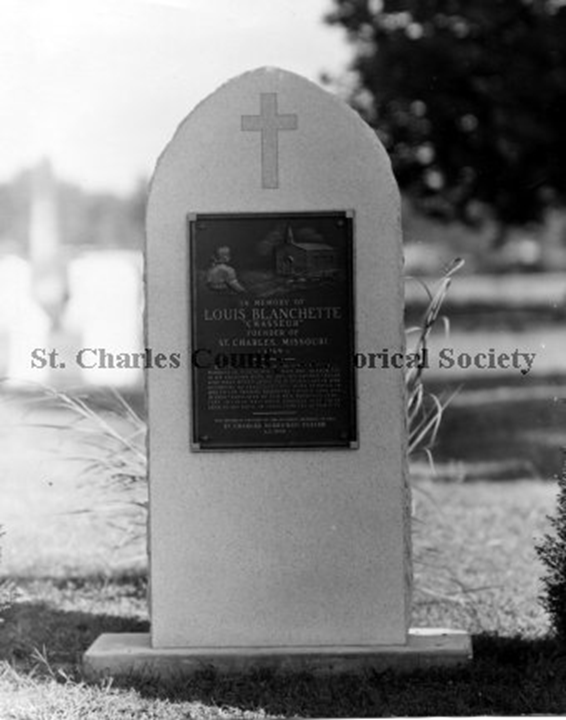

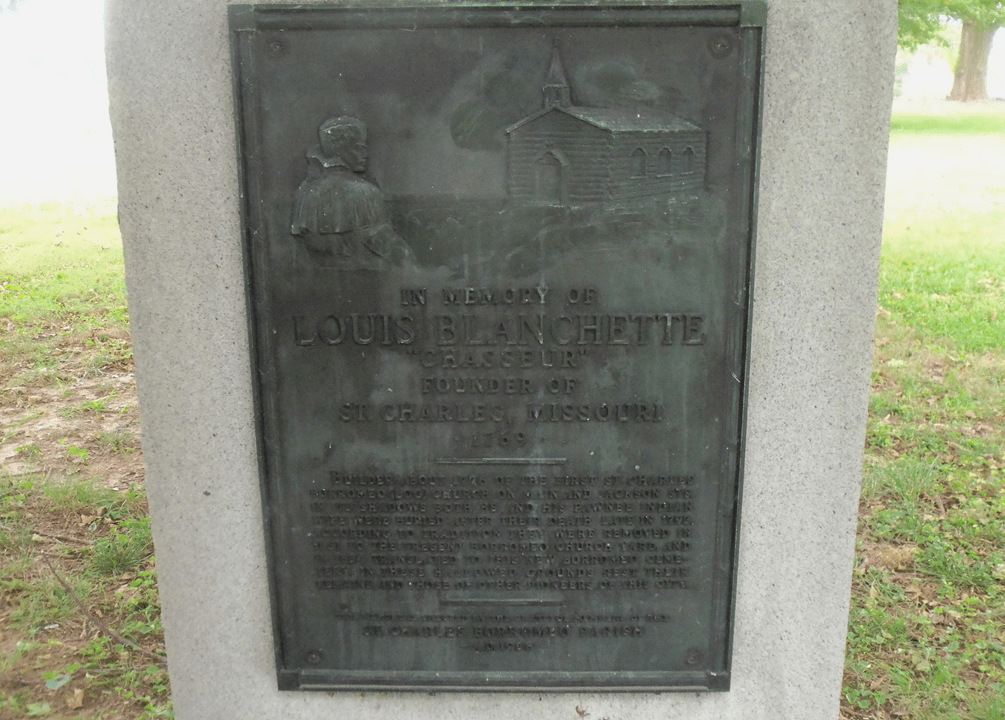

In the twentieth century, Blanchette received posthumous recognition for being the founder of St. Charles. On 7 December 1914, Blanchette Park, the city’s first park, was named for him.[85] Standard Oil Company’s steamer Louis Blanchette was sunk by a German submarine forty miles east of Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1918 (The Cainsville (MO) News, 15 August 1918, p. 6, Newspapers). The local Kiwanis club put on a pageant in 1938. It was called “The Spirit of Louis Blanchette,” the script of which was written by Dr. Kate L. Gregg, a professor at Lindenwood College.[86] In 1939, a bronze plaque was placed on the grave of Louis Blanchette in St. Charles Borromeo Cemetery by St. Charles Borromeo Catholic Church.[87]

1939 marker of Louis Blanchette

SCCHS Photo 21.1.098, photo taken in 1970

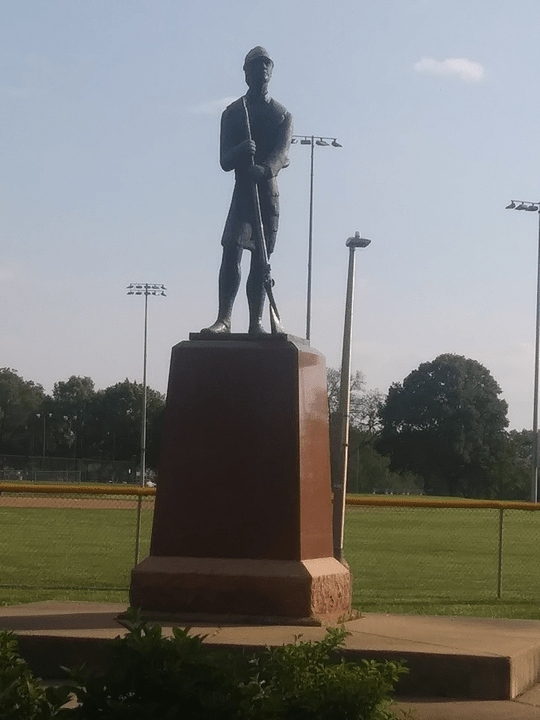

Blanchette received recognition again at the 150th anniversary of the naming of St. Charles (reputed to have occurred at the same time as the dedication of St. Charles Borromeo Catholic Church) in 1941.[88] Blanchette also received honorable mention at the 100th anniversary of St. Peter Catholic Church in St. Charles in 1950.[89] In 1969, one of the goals of the St. Charles Bicentennial celebration was the erection of a statue of Louis Blanchette at Blanchette Park in St. Charles.[90] The statue was officially unveiled at Blanchette Park on 10 August 1971.[91]

Entrance to Blanchette Park, St. Charles, MO

Photograph by Justin Watkins, 2015

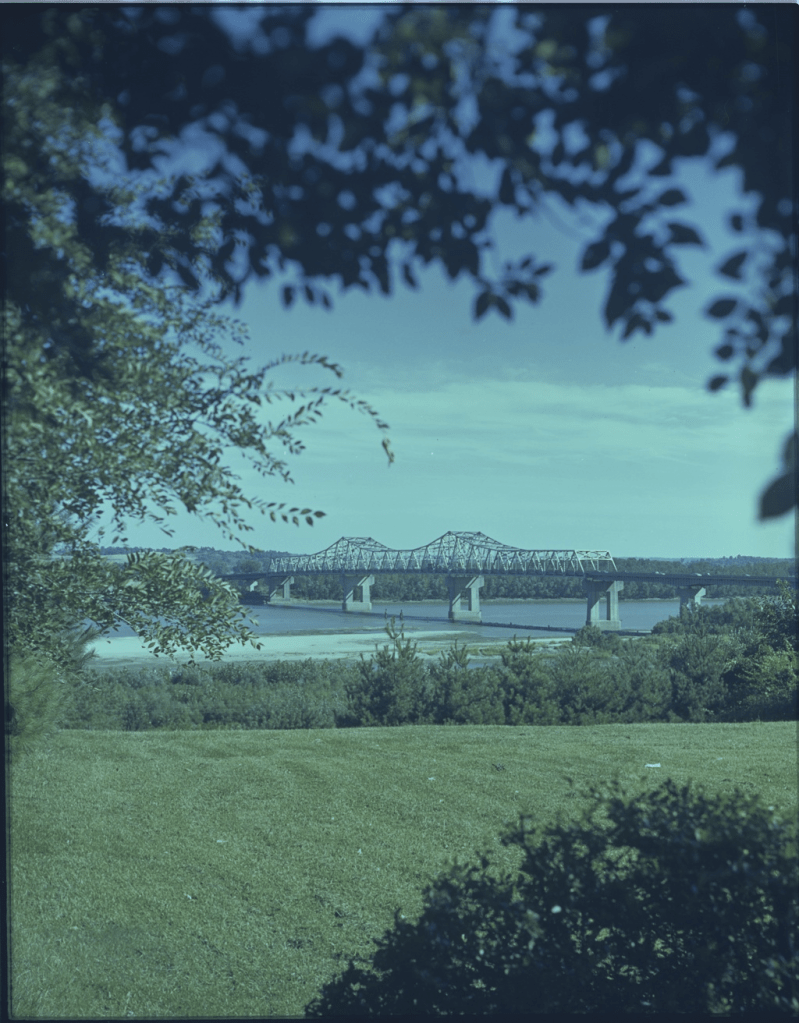

In 1981, the Interstate 70 bridge crossing the Missouri River into St. Charles was renamed the Blanchette Memorial Bridge in honor of Louis Blanchette.[92]

Photo online at https://bridgehunter.com/mo/st-charles/blanchette/

Blanchette received honorable mention again when 906 South Main was the law office of Virginia L. Busch, wife of August A. Busch III of Anheuser-Busch and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch’s Woman of the Year for 1993.[93] 2019 marked the 250th anniversary of Louis Blanchette’s founding of St. Charles. Blanchette continues to be recognized in the names of Blanchette Bridge and Blanchette Park, but, according to Randy Boswell of Postmedia News, “Blanchette’s primary significance was his role in creating the launch pad for westward exploration and settlement—a central narrative of American history.”[94]

[1] Hopewell, Menra, Legends of the Missouri and Mississippi (London: Ward, Lock, and Tyler: 1874), 23-33. Hopewell was an M.D. who practiced in New York City, St. Louis, and later in London, England (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Menra_Hopewell, accessed 10 January 2019)

[2] Baptismal record of Louis-Pierre Blanchette, Quebec Catholic Parish Records, 1621-1979, accessed 10 August 2019

[3] https://www.reference.com/history/discovered-mississippi-river-993083bac05e52fd, accessed 10 August 2019

[4] https://www.usbr.gov/gp/lewisandclark/discovery.html, accessed 10 August 2019

[5] https://www.legendsofamerica.com/mo-stegenevieve/, accessed 10 August 2019

[6] 1885 History of St. Charles County, Missouri, 90-94

[7] http://www.emersonkent.com/historic_documents/treaty_of_fontainebleau_1762_transcript_english.htm, accessed 10 August 2019; https://history.state.gov/milestones/1750-1775/treaty-of-paris, accessed 10 August 2019

[8] http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03231a.htm, accessed 10 August 2019

[9] http://exhibits.museum.state.il.us/exhibits/athome/1700/timeline/index.html, accessed 10 August 2019

[10] http://www.jesuitscentralsouthern.org/aboutus?PAGE=DTN-20140728103917, accessed 10 August 2019

[11] Kelly Moffitt, “Was St. Louis Founded by Laclede and Chouteau?” St. Louis Public Radio, 8 November 2016, https://news.stlpublicradio.org/post/was-st-louis-actually-founded-pierre-lacl-de-and-auguste-chouteau-1764#stream/0, accessed 11 August 2019

[12] Ben L. Emmons, “The Founding of St. Charles and Blanchette Its Founder,” Missouri Historical Review XVIII, no. 4 (July 1924): 512

[13] Hopewell, 23-33

[14] http://www.emersonkent.com/historic_documents/treaty_of_fontainebleau_1762_transcript_english.htm, accessed 10 August 2019; https://history.state.gov/milestones/1750-1775/treaty-of-paris, accessed 10 August 2019

[15] Charles J. Balesi, The Time of the French in the Heart of North America (Chicago: Alliance Française, 1992), 274

[16] http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03231a.htm, accessed 10 August 2019

[17] http://exhibits.museum.state.il.us/exhibits/athome/1700/timeline/index.html, accessed 10 August 2019

[18] http://www.jesuitscentralsouthern.org/aboutus?PAGE=DTN-20140728103917, accessed 10 August 2019

[19] Balesi, 280; https://www.britannica.com/biography/Louis-IX; https://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h2793.html, accessed 10 January 2019

[20] Kelly Moffitt, “Was St. Louis Actually Founded by Pierre Laclède and Auguste Chouteau?” St. Louis Public Radio, 8 November 2016, https://news.stlpublicradio.org/post/was-st-louis-actually-founded-pierre-lacl-de-and-auguste-chouteau-1764#stream/0, accessed 12 August 2019

[21] http://www.carondelethistory.org/about-us.html, accessed 17 August 2019

[22] Bruère and Edwards, 10

[23] James Joseph Conway, Historical Sketch of the Church and Parish of St. Charles Borromeo, St. Charles, MO (1892), 3

[24] “25 and 50 Years Ago,” Alton (IL) Evening Telegraph, 7 December 1956 (Newspaper Archive)

[25] Duane Meyer, The Heritage of Missouri (St. Louis: State Publishing Co., Inc., 1973), 40

[26] “Archaeology Dig Topic of Lecture,” O’Fallon (MO) Journal, 21 January 2009 (NewsBank)

[27] Bruère and Edwards, 10

[28] Rachel Kaatmann, “Dig This: Couple Unearths History,” St. Charles (MO) Journal, 17 September 2006 (NewsBank); Sue Schneider, Old St. Charles (Tucson, AZ: The Patrice Press, 1993), 2

[29] Dr. J. C. Edwards, “St. Charles County,” in Walter Williams, A History of Northeast Missouri (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Co., 1913), 553

[30] Daniel T. Brown, Ph.D., Westering River, Westering Trail (St. Charles, MO: St. Charles County Historical Society, 2006), 81-82

[31] Bruère and Edwards, 10; Louis Houck, A History of Missouri (Chicago: R. R. Donnelley and Sons Co., 1908) II: 83

[32] See St. Charles (MO) Daily Cosmos-Monitor, 14 February 1916 (Newspaper Archive), a transcript of which was done by John J. Buse and included his scrapbook, which is part of the John J. Buse Historical Collection at the State Historical Society of Missouri-St. Louis Research Center. Buse has a separate transcription in his notebook of Edwards’ article from 3 April 1915.

[33] American State Papers, Public Lands II: 588, http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsp&fileName=029/llsp029.db&recNum=603, accessed 10 January 2019

[34] Emmons, 509, cites Hunt’s Minutes IV: 212, No such book and page exist for Hunt’s Minutes at the Headquarters Branch of the St. Louis County Library (microfilm) or in the typescript at the Missouri History Museum’s Library and Research Center

[35] Carr Edwards, St. Charles (MO) Daily Cosmos-Monitor, 14 February 1916; http://www.uscfc.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/court_info/Court_History_Brochure.pdf

[36] Hunt’s Minutes I: 151 – Note: no mention is made of this block being given by Louis Blanchet to John Coontz. On this block, John Coontz built a mill in 1795 according to the testimony of Romain Dufreine.

[37] Deed Book D, 313, 28 April 1817

[38] Daughters of the American Revolution Magazine LVI, no. 7 (July 1922): 405; “D.A.R. Celebration at St. Charles Next Week,” St. Charles (MO) Daily Cosmos-Monitor, 1 October 1921 (Newspaper Archive); the marker was dedicated October 1921. A picture of it can be seen in Dianna and Don Graveman, St. Charles: Les Petites Côtes (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing Co., 2009), 12. Subsequent authors who have placed Blanchette’s house at 906 S. Main Street include the Graveman book; Vicki Berger Erwin and Jessica Dreyer, Then & Now: St. Charles (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing Co., 2011), 18; Brown, 103; Edna McElhiney Olson, Historical Saint Charles, Missouri (St. Charles, MO: St. Charles County Historical Society, 1967), 59; Malcolm Drummond, Historic Sites in St. Charles County (St. Louis: Harland, Bartholomew and Associates, 1976), 37; Edna McElhiney Olson, “Historical Blanchette Home,” St. Charles (MO) Journal, 30 June 1960; Rory Riddler, For King, Cross, & Country (St. Charles, MO: City of St. Charles, 2019), 41-42, attempts to create a synthesis by suggesting that confusion concerning the location of Blanchet’s house. Based on the history of the location of the Blanchet house (as documented in this paper), I reject this conclusion as not recognizing that Block 19 was the first place of identification. It is my opinion that the identification of Blanchet’s house as being in Block 20 was the result of wishful thinking on the part of the organizers of St. Charles’ 1909 centennial. I believe that Latrail’s locating of the first house in St. Charles in Block 19 is contemporary testimony of where Blanchet’s house in reference to the city block system that came later. Also, the fact that this identification pre-dates the Block 20 identification by ninety years leads me to lean toward Block 19 as being the correct identification.

[39] Troy (MO) Free Press, 5 February 1909 (Newspaper Archive)

[40] “Why Not an Arch?” St. Charles (MO) Daily Cosmos-Monitor, 9 August 1921 (Newspaper Archive)

[41] Emmons, 511

[42] Blanchet, 147

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid., 145

[45] Cleta M. Flynn, St. Charles County, Missouri History: Through A Woman’s Eyes (St. Charles, MO: St. Charles County Historical Society, 2014), 3

[46] Emmons, 511

[47] Ibid., 518

[48] L. U. Reavis, Saint Louis: The Future Great City of the World (St. Louis: C. R. Barns, 1876), 318

[49] Williams, 553; Bruère and Edwards, 10; Blanchet, 147 states that the name changed from Les Petites Côtes to Villages des Côtes in 1784; “Le Village des Cotes,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 30 November 1888

[50] Emmons, 508-509; Emmons cites Hunt’s Minutes III: 92

[51] Houck II: 80; see also Mitzi Smith, “Birth of St. Charles,” 2

[52] Emmons, 509; Emmons cites Hunt’s Minutes affidavit, 18 April 1825 (Hunt’s Minutes I: 109)

[53] Emmons, 514

[54] Ibid., 509. Emmons cites Hunt’s Minutes IV: 212; this citation does not check out – no such volume and page appear to exist for Hunt’s Minutes; see also https://s1.sos.mo.gov/records/archives/archivesdb/ViewImages.aspx?Id=567154

[55] Ibid., 511. Emmons cites the Wilson Primm Scrapbook, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis. See also Rory Riddler, For King, Cross & Country (St. Charles, MO: The City of St. Charles), 29

[56] Houck II: 80; Emmons 515; St. Louis, MO, Marriage Book D-3, page 15 in St. Louis, Missouri, Marriage Index, 1804-1876 (St. Louis: St. Louis Genealogical Society, 1999), online at www.ancestry.com, accessed 12 January 2019

[57] “Literary News: Illinois,” 1 August 1790, transcribed in A. P. Nasatir, Before Lewis and Clark: Documents Illustrating the History of the Missouri (1785-1804) (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1990), 132

[58] Blanchet, 148

[59] Emmons, 511

[60] Letter from Manuel Perez to Señor Don Estevan Miró, 29 January 1791, transcribed in Nasatir, 143

[61] Valerie Schremp Hahn, “Fort built in 1793 will now guard area’s past,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 12 March 2006

[62] Jean Fields, “A Season of Fear: San Carlos Del Misury, 1792-1793,” St. Charles County Heritage IX, no. 1 (January 1991): 7

[63] Ibid., 9

[64] Ibid., 11

[65] Ibid., 7

[66] Letter from Zenon Trudeau to Baron de Carondelet, 24 September 1792, transcribed in Nasatir, 160

[67] Letter from Baron de Carondelet to Don Zenon Trudeau, 28 November 1792, transcribed in Nasatir, 163

[68] Fields, 12

[69] Letter from Trudeau to Carondelet, 6 May 1793, transcribed in Nasatir, 173

[70] Excerpt from letter from Trudeau to Carondelet, 10 July 1793. The complete translation and transcript can be found in Nasatir, 184

[71] Hahn, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 12 March 2006

[72] Williams, 553

[73] Brown, 26

[74] Saint Charles Archive, Box 1, no. 5, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis

[75] Emmons, 516

[76] Baron de Carondelet Papers, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis

[77] Saint Charles Archive, Box 3, no. 297, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis

[78] St. Charles County Deed Book D, 313, 28 April 1817

[79] Deed Book E, 175, 13 July 1818

[80] Deed Book G, 402, 28 August 1818

[81] Missouri Gazette and Public Advertiser, Friday, 16 October 1818 (Newspapers)

[82] Deed Book H, 378, 28 December 1828

[83] “More Early History of L. Blanchette,” St. Charles (MO) Daily Cosmos-Monitor, 10 September 1941 (Newspaper Archive)

[84] Deed Book H, 378, 20 April 1829

[85] “Naming City’s First Park: Kansteiner Urged Honor,” St. Charles (MO) Journal, 29 July 1971 (Newspaper Archive)

[86] St. Louis (MO) Star-Times, 10 September 1938 (Newspapers)

[87] “Memorial Will be Erected for Founder of St. Charles,” Marthasville (MO) Record, 13 January 1939 (Newspapers); “Monument Honoring Louis Blanchette Erected in Cemetery,” St. Charles (MO) Daily Cosmos-Monitor, 5 January 1939 (Newspaper Archive)

[88] “St. Charles Church to Keep Its 150th Anniversary,” St. Louis (MO) Post-Dispatch, 5 October 1941 (Newspapers); “Plans Made for Street Parade at Coming Celebration,” St. Charles (MO) Daily Cosmos-Monitor, 12 September 1941 (Newspaper Archive)

[89] St. Charles (MO) Daily Cosmos-Monitor, 1 May 1950 (Newspaper Archive)

[90] St. Louis (MO) Post-Dispatch, 17 August 1969 (Newspapers)

[91] “Naming City’s First Park: Kansteiner Urged Honor,” St. Charles (MO) Journal, 29 July 1971 (Newspaper Archive); “Missouri is 150 Today,” Atchison (KS) Daily Globe, 10 August 1971 (Newspaper Archive); “State Reaches 150th Birthday,” Carthage (MO) Press, 10 August 1971 (Newspaper Archive); “State’s Birthday Today,” Sedalia (MO) Democrat, 10 August 1971 (Newspaper Archive); “Return of Blanchette,” St. Charles (MO) Journal, 12 August 1971 (Newspaper Archive)

[92] Richard H. Weiss, “Main Street,” St. Charles (MO) Post, 29 January 1981 (Newspapers)

[93] “Woman of the Year,” St. Louis (MO) Post-Dispatch, 7 March 1993 (Newspapers)

[94] Randy Boswell, Montreal (Canada) Gazette, 14 June 2011 (Newspapers)

Ben Gall in the April 2022 edition of the St. Charles County Heritage has found reference to Louis Blanchet in the early records of Ste. Genevieve, Missouri (Collection C3636): https://collections.shsmo.org/manuscripts/columbia/c3636

LikeLike

Ben Gall in the St. Charles County Heritage XL (no. 2): 65-67 (April 2022) has found Blanchette mentioned in the early Ste. Genevieve archives. See https://collections.shsmo.org/manuscripts/columbia/c3636 for collection information.

LikeLike